Effect of Additive Manufacturing Parameters on 316L Mechanical and Corrosion Behavior

Materials Science受け取った 24 Oct 2025 受け入れられた 19 Nov 2025 オンラインで公開された 20 Nov 2025

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

受け取った 24 Oct 2025 受け入れられた 19 Nov 2025 オンラインで公開された 20 Nov 2025

Laser Bed Powder Fusion (LBPF) has significantly simplified and accelerated solving complex design challenges, owing to the design flexibility it introduces to additive manufacturing. This technology enables the creation of innovative structures and intricate geometries in a single processing step, in contrast to conventional manufacturing techniques that necessitate multiple stages. Consequently, LBPF lowers production costs, shortens time to market, and enhances the rapid replenishment of stock components. To assess and validate the additive manufacturing process across various applications, it is essential to examine the mechanical, microstructural, and, in certain instances, corrosion characteristics of the materials. The impact of different additive manufacturing laser printing parameters with the goal of enhancing production speed and the quality of parts fabricated from 316L stainless steel, while maintaining mechanical properties and corrosion resistance, was analyzed. This involves selectively adjusting parameters such as laser power, hatch spacing, and laser speed for 20-micron layers that were compared to our standard 40-micron layer parameters. Additionally, evaluations of metallurgical, mechanical, and electrochemical potentiodynamic (corrosion) properties are conducted.

When compared to traditional manufacturing, Additive Manufacturing (AM) of metals offers many advantages, including faster production, the ability to create complicated geometries, shorter time to market, and more. Because of this, AM is a wise investment for several businesses as the technology is reasonably priced [-]. Because of the rough surface finish of these parts, AM of LBPF parts still needs to be machined when tight tolerances are a requirement, as in the case of threads and bores []. As a result, there have been numerous attempts to try and shorten the overall manufacturing time of the finished product, either by creating hybrid AM systems with CNC capabilities [] or by improving the material's intrinsic properties to make it easier to machine [].

This study examines the impact of altering processing parameters during LBPF, specifically the influence of layer height on corrosion characteristics. However, as this parameter is usually used to quantify the quality of solidification of a part, the effect on the build's total energy density (E) must be considered when adjusting a build's layer height as well [,].

The energy density is characterized by several parameters, including power, laser speed (mm/s), layer height (mm), and hatch spacing (mm). Adjustments to these parameters can be made to maintain a high volume energy density. Through a trial and error process, one can identify the optimal combination of these properties that yields mechanically robust builds of 20-micron 316L stainless steel and expedite manufacturing times with higher resolutions. These parameters build upon and expand the findings of a prior study []. Therefore, this work aims to explore the mechanical and corrosion behavior of parts printed using high-resolution build parameters (20-micron build height) that will limit the amount of post-processing compared to standard printing parameters.

The wrought and AM 316L rods' chemical composition was compatible. The wrought rods were taken off the shelf and were in the annealed condition. The AM rods post-processing was performed in-house for a similar anneal (in the stress-relieved condition for 400 oC for 1 hour).

All samples were fabricated utilizing 316L powder sourced from 6K Additive, characterized by a particle size distribution ranging from 5 to 50 micrometers. The printing process was conducted on an EOS M290 machine, employing a hard recoated blade with a spot size of 100 micrometers and a scanning pattern that rotates at an angle of 37 degrees. Cylindrical bars measuring 18 mm in diameter and 85mm in length were produced according to the parameters detailed in Table 1, which includes both standard and experimental parameters (designated as A, B, C, D, and E for the wrought bar).

The AM bars were later machined on a Tormach lathe to meet ASTM E8 standards for tensile testing.

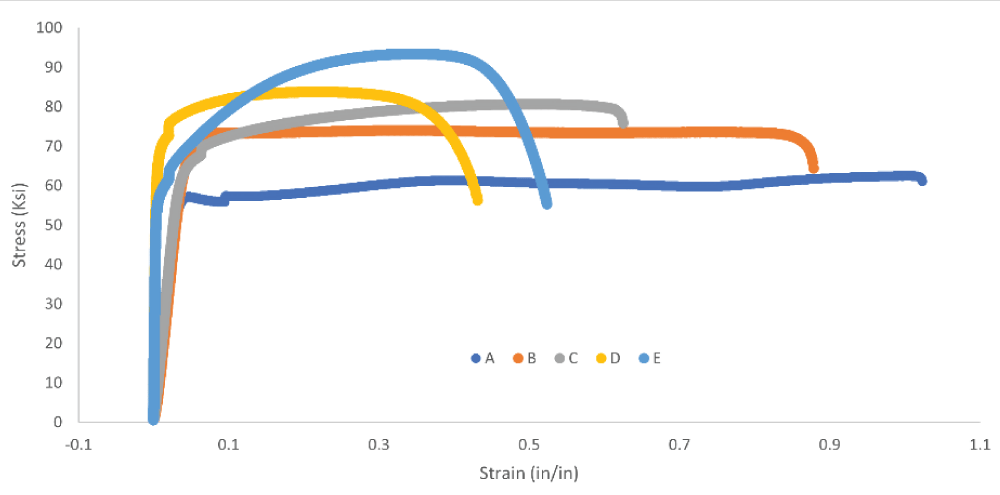

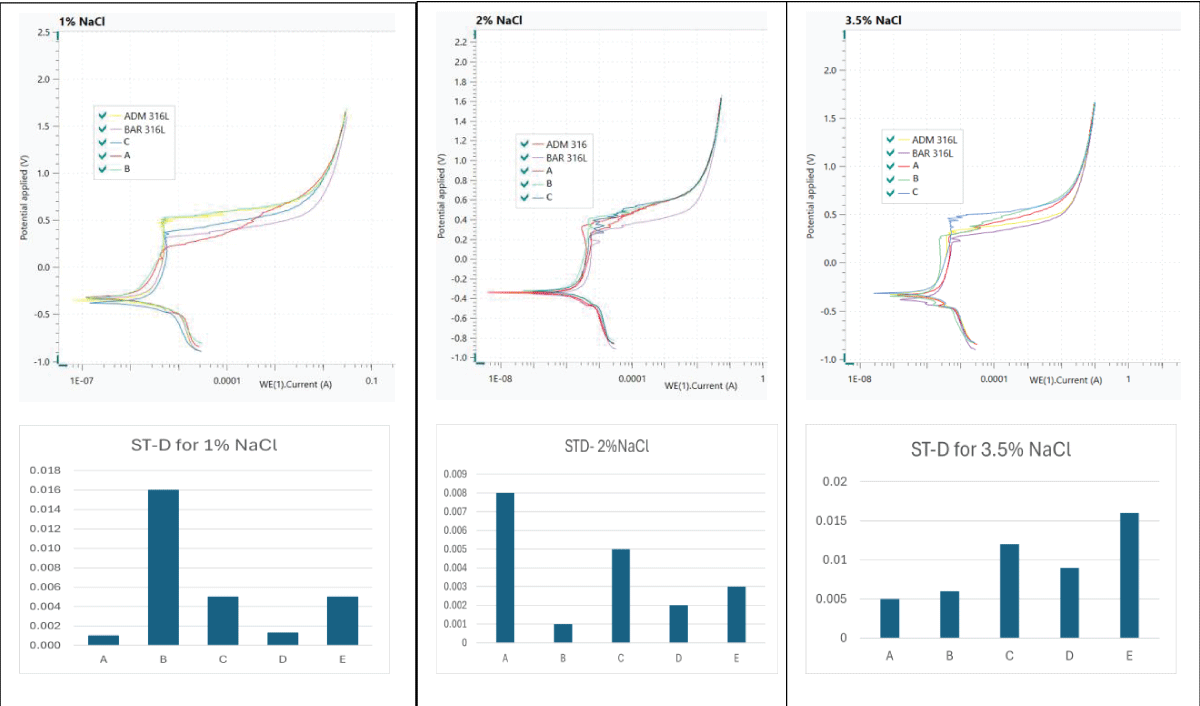

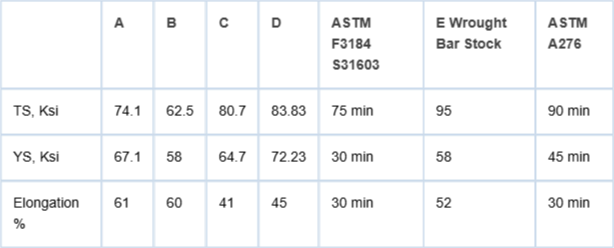

The tensile tests were conducted using United FM-60, with a 60K (300KN) load cell at room temperature and normal lab atmosphere, following ASTM E8 standard with a speed of 0.05 mm/mm [or in./in.] Stress-strain plots were created from the data to characterize the mechanical properties of each bar. Tensile tests are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Figure 1: Stress-strain curves of printed samples with different build parameters (A, B, C, D) compared with wrought bar stock (E).

Figure 1: Stress-strain curves of printed samples with different build parameters (A, B, C, D) compared with wrought bar stock (E).Electrochemical experiments were performed using a standard three-electrode flat cell system connected to a potentiostat [Metrohm Autolab, PGSTAT 204]. An Ag/AgCl type reference electrode was used, while dual stainless-steel rods were used as the counter electrodes. Before each test, working electrodes were first polished sequentially using silicon carbide paper to grade #2400 paper. They were then rinsed with deionized water (with resistivity of 18 MΩ.cm · cm) followed by ethanol, and finally air dried. Samples were stored in a dry chamber until testing.

Working electrodes were inserted into a Teflon holder with an exposed surface of 1 cm2 to the testing solution. Before testing, a cathodic conditioning at -0.5V vs. Eocp (open circuit potential) for 6 minutes was performed, thereby removing possible surface oxide layer formation. The polarization scans were recorded in aerated 1%, 2%, and 3.5% NaCl solutions. After the stabilization of the open circuit potential (OCP) of the electrochemical system, electrochemical measurements were performed. In the potentiodynamic polarization measurement, the working electrodes were scanned in the potential range of −0.6 to +1.6V with respect to the OCP value. The scan rate employed was 0.01 V/s. The measurements were repeated three times for each of the solutions for reproducibility, and the mean values were taken. Images of the control and corroded samples' surface morphologies were analyzed using optical microscopy.

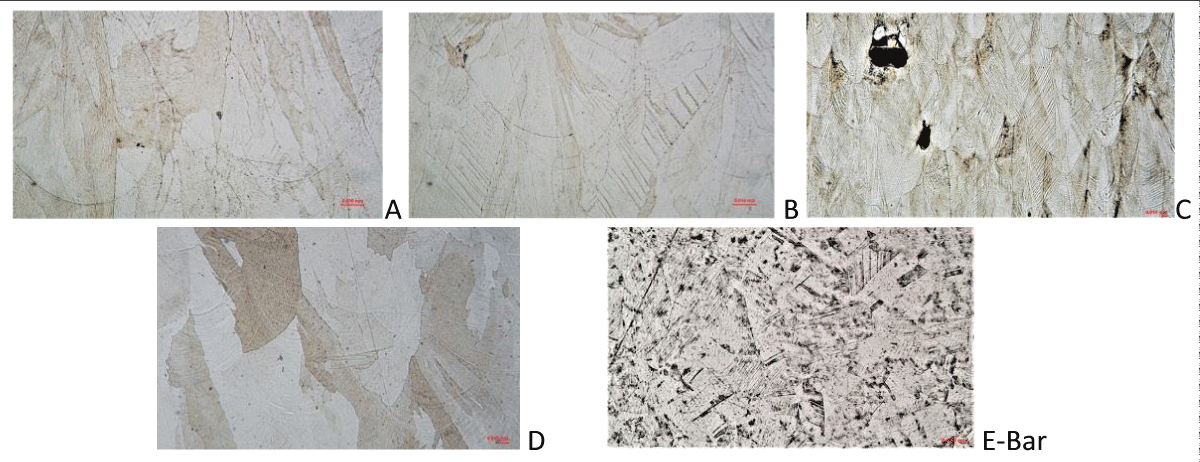

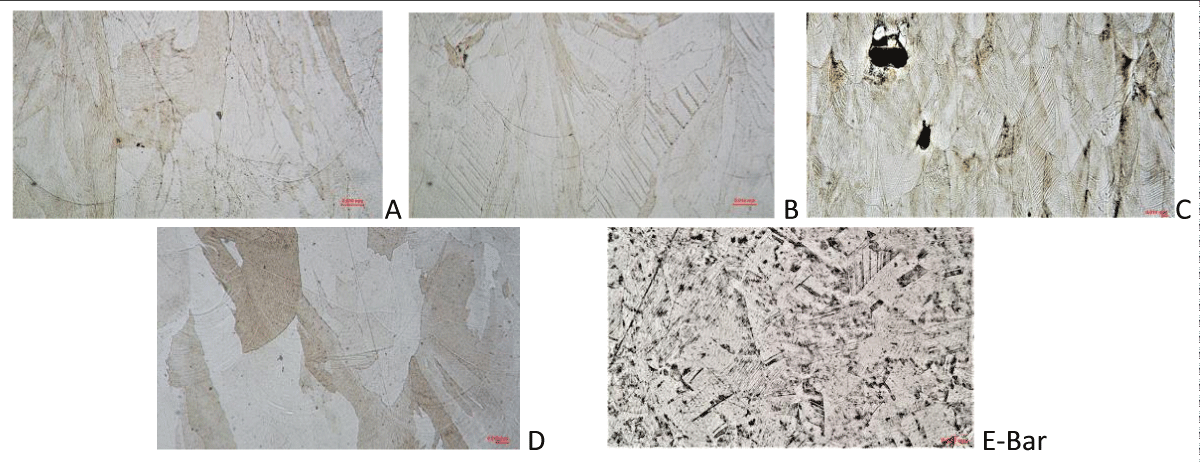

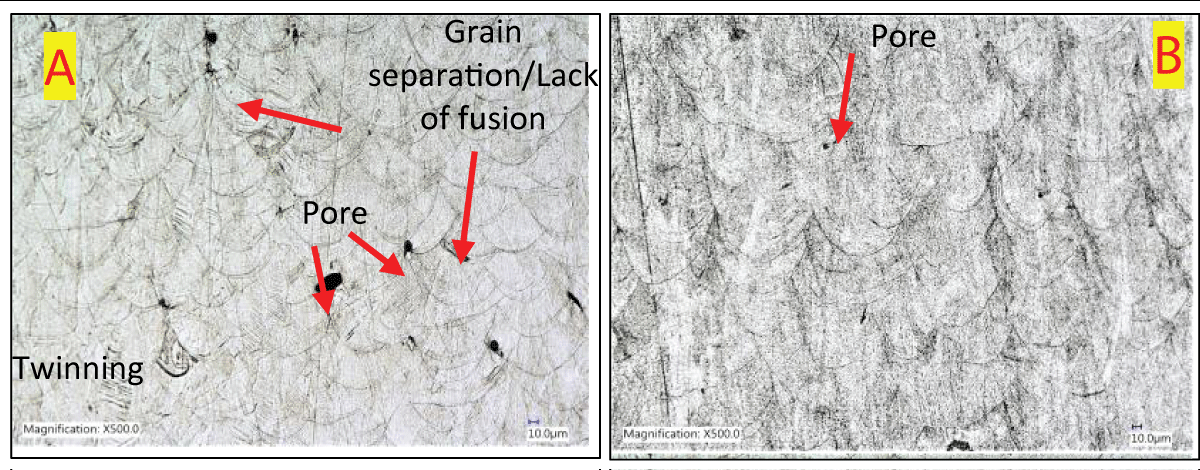

Microstructural evaluation was performed on a cross-section taken from tensile bars of each specimen built and each electrochemical test sample. Samples were analyzed along the length for microstructure features shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Optical micrographs of samples showing various defects at different speed and hatch spacing, in etched condition, and wrought bar in as received condition “E”.

Figure 3: Optical micrographs of samples showing various defects at different speed and hatch spacing, in etched condition, and wrought bar in as received condition “E”.Vickers hardness tests were conducted at room temperature using a Metkon DUROLINE LV4 micro Vickers hardness tester, with a load of 300gf.

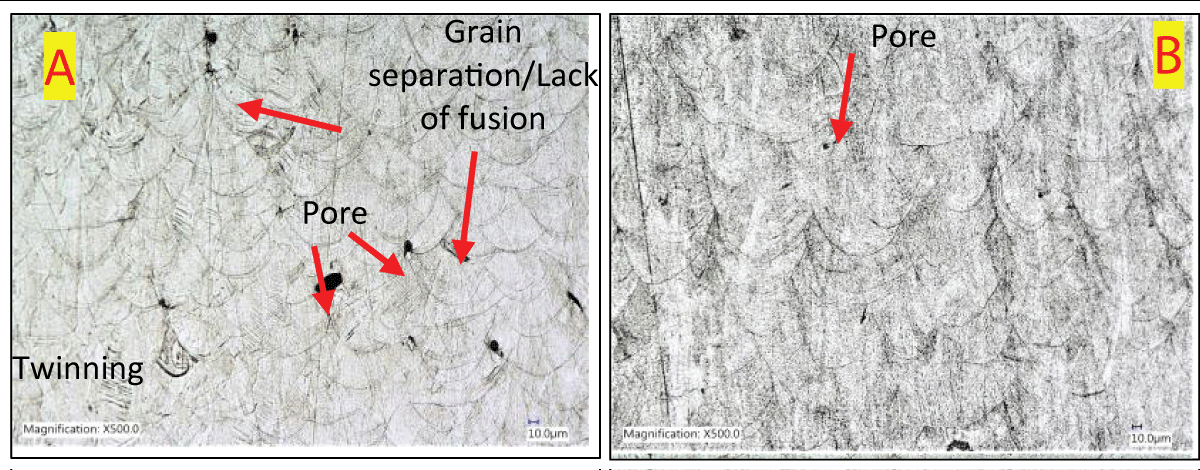

The objective of this work was to evaluate the effect of varying printing parameters: scanning speed, layer thickness, scan patterns, and laser power, as established in a previous study [] have on microstructure and corresponding corrosion behavior. These parameters, individually or combined, can influence the final microstructural product or part, and hence its mechanical and corrosion properties. Some examples of the defects due to processing are dislocations, lack of fusion, cracks, pores (common in high laser energy density), anomalous microstructure (martensite formation), and the balling effect. Balling effect can be distinguished from unmelted particle(s) only by metallography, revealing solidification structure layer(s). This phenomenon will occur when the molten layer does not wet the substrate due to surface tension. This leads to spheroidization of the liquid, resulting in a bead-shaped surface, preventing smooth layer deposition, thereby decreasing the density of the final part build [,].

The AM samples exhibited similar core microstructural features with varying levels of porosity. Internal structure revealed local irregularities, particularly between layers, possibly because of lower energy, resulting in lack-of-fusion areas (Figures 3,4). In addition, deformation twinning, induced plasticity were revealed from metallographic samples. It is believed that deformation twinning is attributed to the enhanced ductility of the tested samples, despite porosity being found [].

Figure 4: Optical micrographs of samples showing various defects at different speed and hatch spacing, in etched condition.

Figure 4: Optical micrographs of samples showing various defects at different speed and hatch spacing, in etched condition.This effect was observed in the tensile test results, where the elongation of some of the bars was higher than others. Ductility was enhanced by twinning for some samples, as found previously []. The microstructure of twinning and martensite can be differentiated from twinning, as this martensitic transformation is mainly a local manifestation or change, while twinning can take up an entire lattice. On the other hand, α′ and ε-martensite can also be differentiated as α′-martensite normally nucleates at dislocation pile-up, while ε-martensite nucleates at staking faults [-]. The martensite formed is most likely by γ-α′-transformation during plastic deformation in the tensile test [].

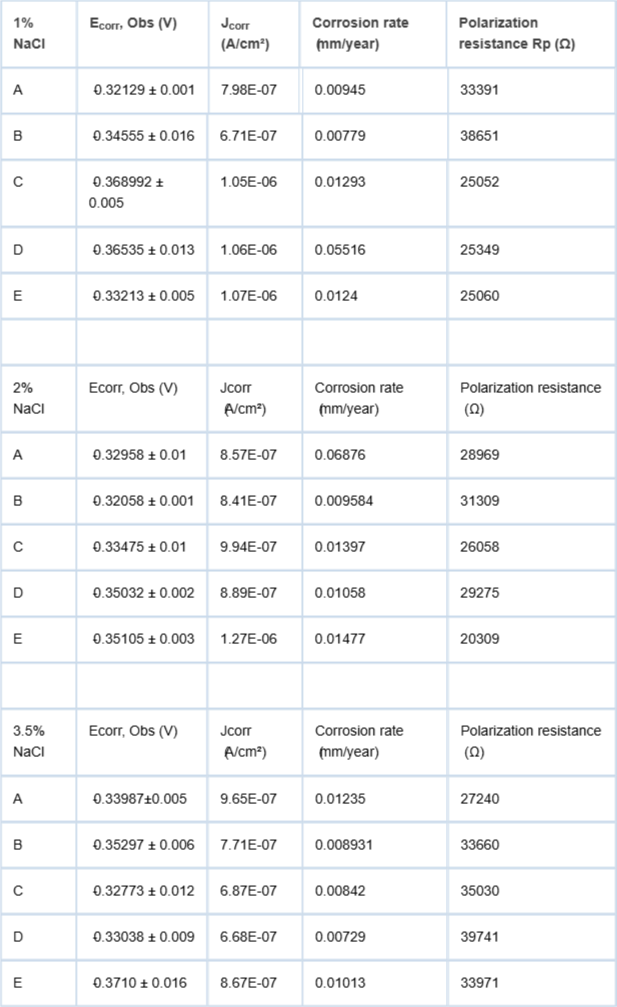

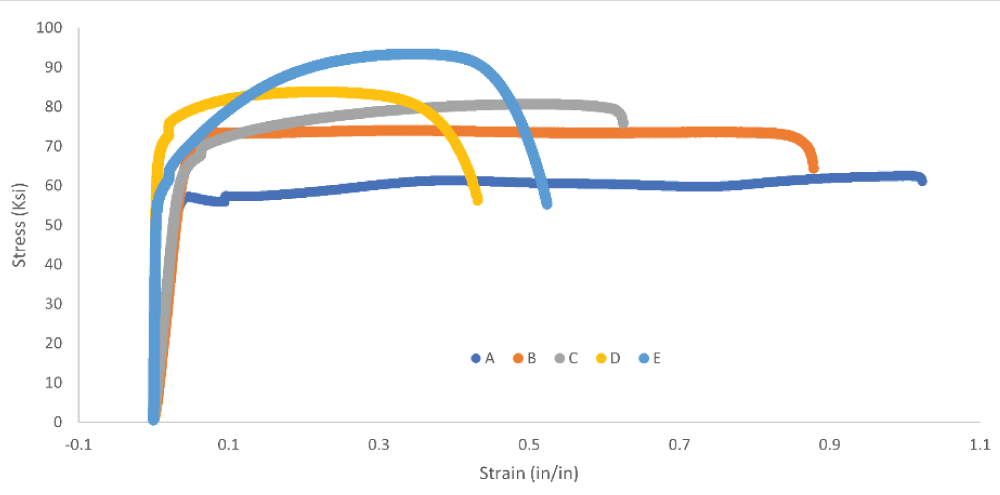

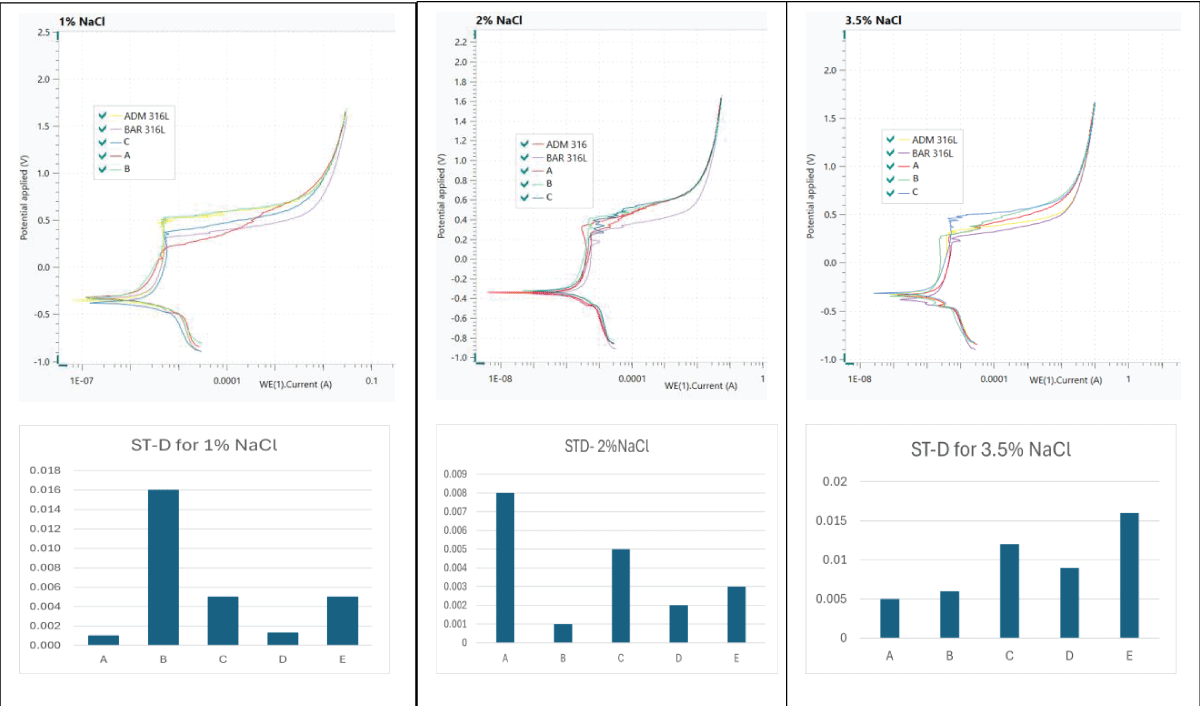

The potentiodynamic polarization curves of type 316L AM with different process parameters and a wrought sample were conducted at room temperature, which was aerated in 3.5% NaCl solution at scan rates from 0.01. The results of the testing are shown in Figure 3. All samples showed a typical anodic polarization behavior of a stainless steel in a NaCl solution consisting of active dissolution, passivity, and a rapid increase in the current density due to pitting. The results indicated that dissolved oxygen is the main source of cathodic reaction in aerated solutions. The cathodic current decreases as the potential increases in the positive direction until it reaches Ecorr. In addition, hydrogen evolution and oxidation reactions were observed during the corrosion process.

This rapid increase in the current density indicates the occurrence of stable pitting in which the potential corresponding to this current transient transition is known as a critical pitting potential (Epit). Scan rates showed stable pit growth during the polarization. Some current density spikes are observed at potentials below Epit. These spikes are due to the occurrence of metastable pits and are explained by the consecutive formation and repassivation of micro-sized pits []. Comparing the three curves together, the frequency and magnitudes of the spikes appear to increase with the potential.

The fluctuations in the recorded currents for all samples indicate there is vulnerability of the stainless-steel passive film during de-passivation/repassivation periods in testing. Only the AM-316L sample revealed less damage. In all tests, better corrosion behavior was found in AM parts compared to the wrought counterpart (“E”), with less corrosion seen on the AM samples with slight variations among the different printing parameters (A-D). Internal defects in AM parts, irrelevant of the type, distribution, and/or clustering, are generally randomly distributed with the porosity volume amount related to the printing parameters. This means that porosity was random in each test sample, and is removed from a bar, but would generally be the same from each sectioned piece for each test condition (A-D).

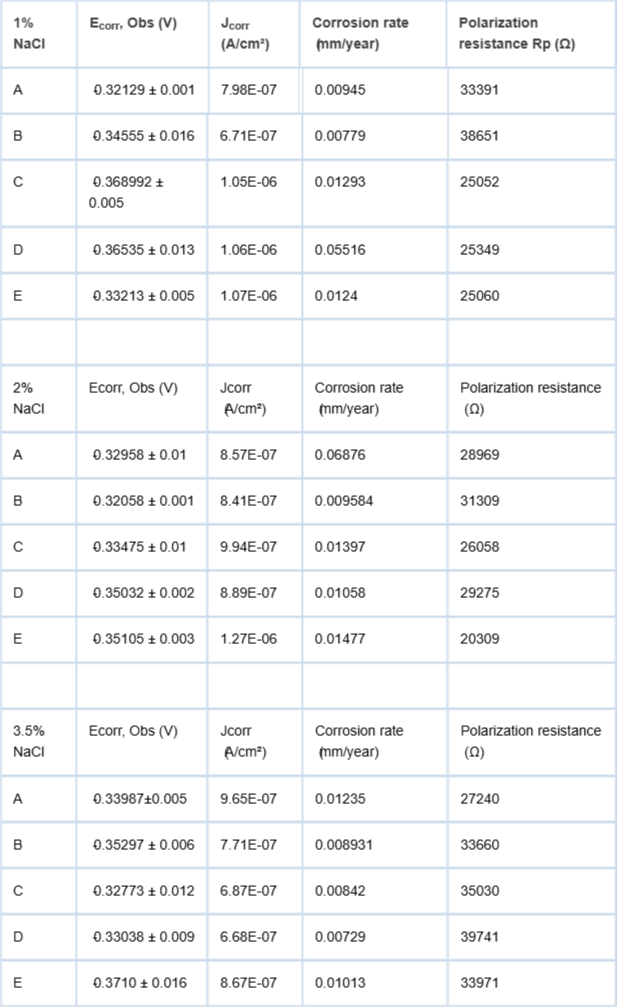

The wrought bar samples had the smallest passive window polarization results in 2% and 3.5% NaCl solutions. Interestingly, AM sample B had the lowest corrosion rate in 1% and 2% NaCl solutions shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Corrosion polarization average results for the test in 1%, 2%, and 3.5% NaCl, arranged with increasing corrosion rate, mean values recorded with standard deviation.

Table 3: Corrosion polarization average results for the test in 1%, 2%, and 3.5% NaCl, arranged with increasing corrosion rate, mean values recorded with standard deviation.In the 1% NaCl solutions, the as-printed AM 316L SS “D” and “B” displayed a slightly wider passive window than the other printed AM-316L SS samples “C, A” and wrought, in addition to metastable pitting polarization Eb beyond 0.5V for sample “A”, ∼0.3V for wrought, ∼0.4V for “C”, and ∼0.57V for AM and “B” all vs. Ag/AgCl.

In the 2% NaCl solutions, the as-printed AM 316L displayed a better passive window with the least metastable pitting with Eb 0.35V, while ∼0.15V for wrought, ∼0.30 for sample “A”, ∼0.33V for sample “B”, and ∼ 0.25V for sample “C” all vs. Ag/AgCl.

In the 3.5% NaCl solutions, as-printed AM 316L sample “D” had the lowest corrosion rate, followed by sample “C”, “B”, “E-bar stock”, and “A”. Pitting potential for as-printed AM 316L and sample “B” 0.25V, 0.35V for sample “C”, ∼0.3V for sample “A”, and ∼0.2V all vs. Ag/AgCl (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Representative potentiodynamic measurements for all samples in all solutions, 1%, 2%, and 3.5% NaCl, ADM is as printed (AM samples) without change in parameters, A, B, and C printed with adjusted parameters, and wrought bar stock, along with standard deviation.

Figure 5: Representative potentiodynamic measurements for all samples in all solutions, 1%, 2%, and 3.5% NaCl, ADM is as printed (AM samples) without change in parameters, A, B, and C printed with adjusted parameters, and wrought bar stock, along with standard deviation.It is interesting to note that an increase in NaCl concentration is accompanied by a reduction in aeration effects and, in turn, inversely impacts corrosion rates to a limit. This is because when the salt percentage is increased, there is a resulting reduction in dissolved oxygen, and this reduces the stability of the protective passive film. This, in part, explains the slightly higher corrosion rate results for some of the samples, 1% to 3.5%. This observation may not apply to other alloys that will not spontaneously develop protective films, leading to an increase in corrosion rate. Other alloys that do not develop a good adherent oxide layer per Pilling-Bedworth ratio might develop pits or undergo general corrosion, such as pure iron (Fe).

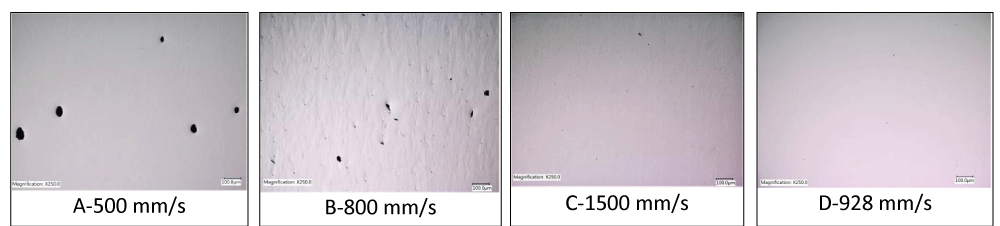

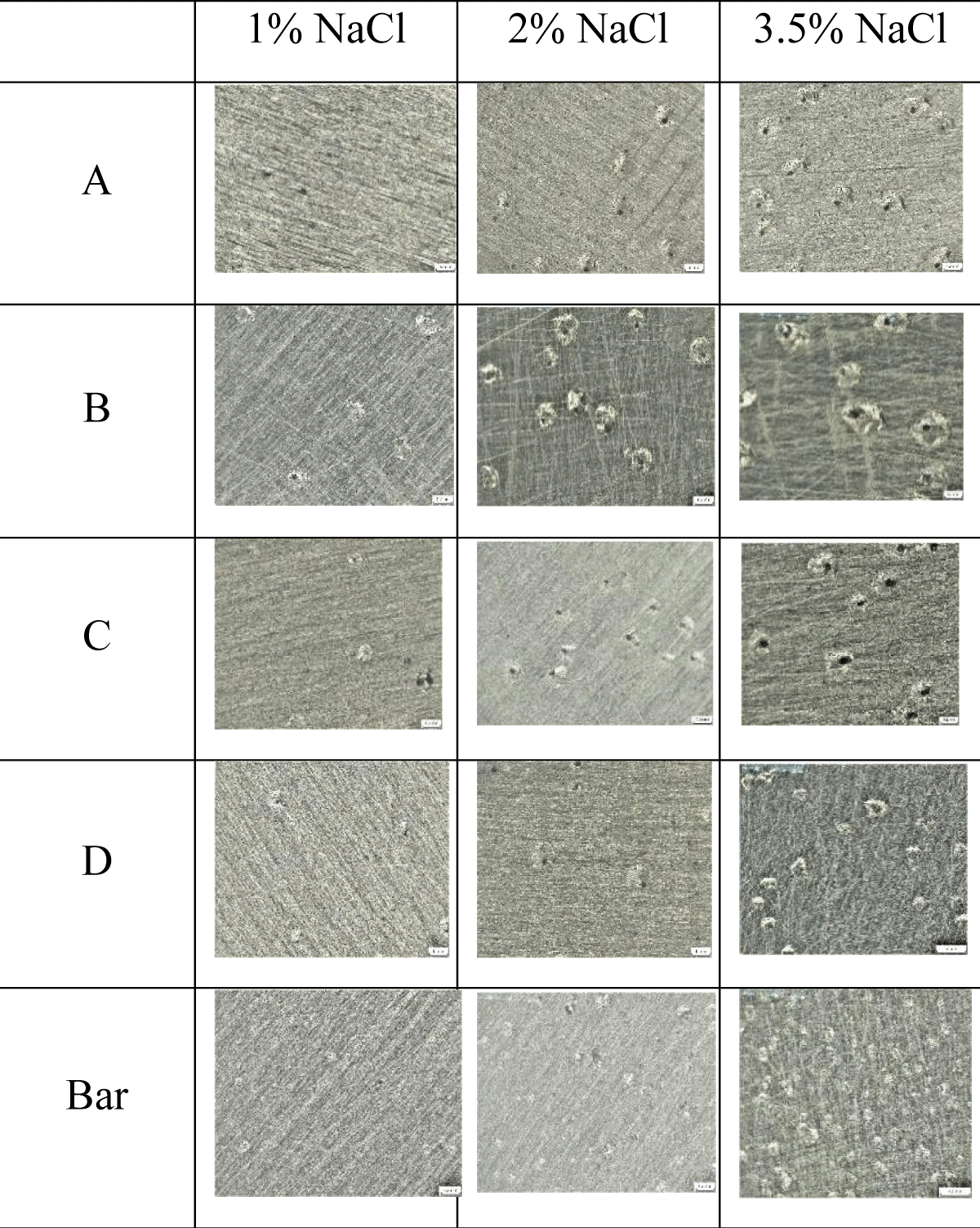

The corrosion attack in all samples was in the form of pitting corrosion (Figure 4) that was evenly scattered on the surface. Samples A, B, and C showed more pitting with wider openings than the wrought sample, with the least found in the D sample. Therefore, it seems that standard parameters with a larger layer height have larger grains that are better for targeted pitting corrosion. All 20 microns build much smaller grains due to the smaller layer height (Figure 3), which likely experienced more melting and remelting that leading to a finer grain structure. However, when looking at corrosion rate in the low concentration 1% NaCl, the 20 micron builds (A-C) showed slower rates (Table 3). This is likely due to the many grains providing many sites for quickly passivating the surface in low-salinity environments. In the higher concentration (3.5%), the effect may be too much, damaging multiple grains unable to passivate, leading to the standard build parameters (D) having the best corrosion rate (Figure 6).

The pitting properties of LBPF AM SS316L and bar stock SS316L in NaCl solutions were investigated using potentiodynamic polarization techniques. The AM SS316L electrochemical performance was made slightly better with printing parameter modifications and had performance nearly the same as its counterpart wrought alloy.

The potential for creating printing variables to enhance production speed, while permitting minor internal defects, had minimal impact on the corrosion rate, provided that the intended process loading remains static. Furthermore, the standard AM printing parameters led to superior mechanical results. The marginally reduced corrosion performance of the wrought 316L can likely be ascribed to the presence of inherent non-metallic inclusions of the foundry process.

Mechanical properties of the samples fabricated using the printing strategies of samples A and B produced lower yield strength and ultimate tensile strength values than sample C, D (standard parameters), and the wrought counterpart. The lower results can be attributed to the resultant internal defects, such as porosity.

The overall findings are promising to support further research aimed at improving the delivery time of additively manufactured components, while ensuring the preservation of strength, ductility, and corrosion resistance.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Yadroitsev I, Thivillon L, Bertrand P, Smurov I. Strategy of manufacturing components with a designed internal structure by selective laser melting of metallic powder. Appl Surf Sci. 2007;254:980-3.

Ferro P, Meneghello R, Savio G, Berto F. A modified volumetric energy density–based approach for porosity assessment in additive manufacturing process design. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020;110.

Rombouts M, Kruth JP, Froyen L, Mercelis P. Fundamentals of selective laser melting of alloyed steel powders. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol. 2006;55.

Didier P, Le Coz G, Piotrowski B, Bravetti P, Laheurte P, Moufki A. Post-processing of additive manufactured parts: a numerical strategy applied in maxillary implantology. Mater Tech. 2022;110.

Jiménez A, Bidare P, Hassanin H, Tarlochan F, Dimov S, Essa K. Powder-based laser hybrid additive manufacturing of metals: a review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021;114.

Pérez J, Gonzalez H, Sanz-Calle M, Gómez-Escudero G, Munoa J, López Lacalle L. Machining stability improvement in LBPF printed components through stiffening by crystallographic texture control. CIRP Ann. 2023;72.

Babakr A, Gamboa G. Improving the additive manufacturing of parts for chemical manufacturers. Chem Eng. 2024.

Patil DA. Effects of increasing layer thickness in the laser powder bed fusion of Inconel 718. Tempe (AZ): Arizona State University; 2019;8.

DeCooman BC, Kwon O, Chin KG. State-of-the-knowledge on TWIP steel. Mater Sci Technol. 2012;28:513.

Sato K, Ichinose M, Hirotsu Y, Inoue Y. Effects of deformation-induced phase transformation and twinning on the mechanical properties of austenitic Fe-Mn-Al alloys. ISIJ Int. 1989;29:868.

Dafé SSF, Sicupira FL, Matos FCS, Cruz NS, Moreira DR, Santos DB. Effect of cooling rate on (ε, α') martensite formation in twinning/transformation-induced plasticity Fe-17Mn-0.06C steel. Mater Res. 2013;16:1229.

Michler T, Bruder E. Local strains in 1.4301 austenitic stainless steel with internal hydrogen. Mater Sci Eng A. 2018;725:447-55.

Pessall N, Liu C. Determination of critical pitting potentials of stainless steels in aqueous chloride environments. Electrochim Acta. 1971;16(11).

Babakr A, Gamboa G. Effect of Additive Manufacturing Parameters on 316L Mechanical and Corrosion Behavior. IgMin Res. November 20, 2025; 3(11): 401-406. IgMin ID: igmin321; DOI:10.61927/igmin321; Available at: igmin.link/p321

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

Senior Principal, Materials Engineer (R&D), Emerson – McKinney, Texas, USA

Address Correspondence:

Dr. Ali Babakr, Senior Principal, Materials Engineer (R&D), Emerson – McKinney, Texas, USA, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Babakr A, Gamboa G. Effect of Additive Manufacturing Parameters on 316L Mechanical and Corrosion Behavior. IgMin Res. November 20, 2025; 3(11): 401-406. IgMin ID: igmin321; DOI:10.61927/igmin321; Available at: igmin.link/p321

Copyright: 2025 Babakr A, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Stress-strain curves of printed samples with diffe...

Figure 1: Stress-strain curves of printed samples with diffe...

Figure 2: Representative micrographs of AM samples at varyin...

Figure 2: Representative micrographs of AM samples at varyin...

Figure 3: Optical micrographs of samples showing various def...

Figure 3: Optical micrographs of samples showing various def...

Figure 4: Optical micrographs of samples showing various def...

Figure 4: Optical micrographs of samples showing various def...

Figure 5: Representative potentiodynamic measurements for al...

Figure 5: Representative potentiodynamic measurements for al...

Figure 6: Optical macrographs of samples showing pitting mor...

Figure 6: Optical macrographs of samples showing pitting mor...

![<p>Process parameters used for the production of 316L stainless steel samples by LBPF [7].</p>](https://www.igminresearch.jp/articles/fulltext/table_images/igmin321/Table1.png) Table 1: Process parameters used for the production of 316L...

Table 1: Process parameters used for the production of 316L...

Table 2: Mechanical properties of 316L samples at room temp...

Table 2: Mechanical properties of 316L samples at room temp...

Table 3: Corrosion polarization average results for the tes...

Table 3: Corrosion polarization average results for the tes...

Yadroitsev I, Thivillon L, Bertrand P, Smurov I. Strategy of manufacturing components with a designed internal structure by selective laser melting of metallic powder. Appl Surf Sci. 2007;254:980-3.

Ferro P, Meneghello R, Savio G, Berto F. A modified volumetric energy density–based approach for porosity assessment in additive manufacturing process design. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2020;110.

Rombouts M, Kruth JP, Froyen L, Mercelis P. Fundamentals of selective laser melting of alloyed steel powders. CIRP Ann Manuf Technol. 2006;55.

Didier P, Le Coz G, Piotrowski B, Bravetti P, Laheurte P, Moufki A. Post-processing of additive manufactured parts: a numerical strategy applied in maxillary implantology. Mater Tech. 2022;110.

Jiménez A, Bidare P, Hassanin H, Tarlochan F, Dimov S, Essa K. Powder-based laser hybrid additive manufacturing of metals: a review. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021;114.

Pérez J, Gonzalez H, Sanz-Calle M, Gómez-Escudero G, Munoa J, López Lacalle L. Machining stability improvement in LBPF printed components through stiffening by crystallographic texture control. CIRP Ann. 2023;72.

Babakr A, Gamboa G. Improving the additive manufacturing of parts for chemical manufacturers. Chem Eng. 2024.

Patil DA. Effects of increasing layer thickness in the laser powder bed fusion of Inconel 718. Tempe (AZ): Arizona State University; 2019;8.

DeCooman BC, Kwon O, Chin KG. State-of-the-knowledge on TWIP steel. Mater Sci Technol. 2012;28:513.

Sato K, Ichinose M, Hirotsu Y, Inoue Y. Effects of deformation-induced phase transformation and twinning on the mechanical properties of austenitic Fe-Mn-Al alloys. ISIJ Int. 1989;29:868.

Dafé SSF, Sicupira FL, Matos FCS, Cruz NS, Moreira DR, Santos DB. Effect of cooling rate on (ε, α') martensite formation in twinning/transformation-induced plasticity Fe-17Mn-0.06C steel. Mater Res. 2013;16:1229.

Michler T, Bruder E. Local strains in 1.4301 austenitic stainless steel with internal hydrogen. Mater Sci Eng A. 2018;725:447-55.

Pessall N, Liu C. Determination of critical pitting potentials of stainless steels in aqueous chloride environments. Electrochim Acta. 1971;16(11).