The Cancer Stem Cell Concept as Applied to Prostate Cancer

Oncology受け取った 24 Dec 2025 受け入れられた 21 Jan 2026 オンラインで公開された 22 Jan 2026

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Next Full Text

A Multi-Model Simulation Framework for Sponge Park Concept Achieving Urban Water Energy Nexus Sustainability in Hyper Arid Climates

受け取った 24 Dec 2025 受け入れられた 21 Jan 2026 オンラインで公開された 22 Jan 2026

The cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis proposes that rare tumor-initiating cells with stem-like properties drive cancer progression and metastasis. Through comprehensive analysis of prostate cancer patient-derived xenografts (PDX), we demonstrate that all cancer cell types—not exclusively stem-like cells—can initiate tumors in mice, contradicting a core CSC tenet. CD44, commonly used to identify CSCs, proved inconsistent in prostate cancer. However, stem-like cancer cells do exist, characterized by expression of stem cell transcription factors (scTF LIN28A, NANOG, POU5F1, SOX2) and low β-2 microglobulin (scTF⁺B2Mlo). We show that differentiated adenocarcinomas can be experimentally reprogrammed to stem-like small cell carcinomas through scTF expression, while stromal signaling molecules like proenkephalin (PENK) induce differentiation. These findings reveal that prostate cancer progression involves dynamic dedifferentiation due to loss of stromal signaling rather than clonal expansion of rare CSC. Cancer cells exhibit remarkable plasticity, undergoing reversible differentiation-dedifferentiation cycles independent of mutation burden, suggesting differentiation therapy as a promising treatment strategy.

The cancer stem cell hypothesis posits that a population of cancer cells with stem cell properties is capable of starting, promoting tumor growth, and metastatic spread. Like stem cells, these cancer cells can undergo differentiation into other cancer cell types, producing tumor heterogeneity. Furthermore, cancer stem cells (CSC) are rare, with a frequency of about 10−4 []. We will review based on research in prostate cancer if the CSC description of human solid tumors is applicable point by point.

Xenotransplantation and serial passaging in mice form the basis for demonstrating the existence of CSC, since only they can engraft and propagate tumor growth in vivo. In blood cancer, cell sorting was used to isolate leukemia stem cells (LSC) by targeting the cell surface molecules CD34 and CD38 in samples of acute myeloid leukemia []. The sorted CD34+CD38− cells were able to form tumors in mice, whereas those of CD34+CD38+ and CD34− were not. The formed tumors were serially transplanted to show self-renewal. Furthermore, the passaged tumors contained not only CD34+CD38− but also CD34+CD38+ and CD34− cells. It would appear that these LSC could undergo spontaneous differentiation to produce non-stem progeny, or perhaps under the influence of murine factors at the implantation sites. These results showed that LSC shared properties with hematopoietic stem cells in expressing specific cell surface antigens and undergoing differentiation. In solid tumors, sorted CD44+CD24− breast cancer cells were also shown to possess tumor-forming capability in contrast to CD44+CD24+ or CD44− cells, and at an efficiency of 100-fold less in the number of cells needed []. The serially transplantable tumors in mouse mammary pads were shown to contain the three distinguishable cell types. The resultant cancer cells were postulated to derive from a CD44 precursor. Such findings were extended to brain tumor cells isolated by the stem cell surface marker CD133. Implanted CD133+ tumor cells in the mouse brain were shown to produce both CD133+ and CD133− progeny [,]. Studies from several other tumor types reported similar data.

For prostate cancer, a family of cancer-derived xenografts (PDX) was obtained and characterized []. To establish each PDX, tumor samples of ~20 mg free of other cells, fat, and necrotic tissue were implanted subcutaneously. Tumor growth in mice was monitored over 18 months. A line was deemed established if it survived three passages and was then maintained by continuous passaging in mice. The first generated cohort was derived from >250 donations, which included primary tumors, metastases to the bladder, adrenal gland, local and distant lymph nodes, bone, liver, and bowel. The tally of twenty-six individual lines represented a take rate of 10%, well above that of 10−4 reported for CSC. One could argue that a greater number of tumor cells were implanted to begin with to produce the higher success rate. In success and failure, roughly the same number of cells were implanted. No association between take rate and sample procurement from either surgery or rapid autopsy, or the anatomical sites was found. Initial tumor growth lasted 4-12 months, and a 50% - 80% secondary take rate. Tumor size could achieve 1 g in 4-16 weeks. The different PDX lines varied in growth rates. Castration resistant (CR) variants were obtained by passaging in castrated mice. These LuCaP PDX include androgen receptor (AR)-positive, well-differentiated and less differentiated adenocarcinomas, plus AR-negative neuroendocrine small cell carcinoma. AR expression is associated with differentiation. These PDX retained the genomic and expression signatures such as AR amplification, AR mutation, AR splice variants, loss of PTEN and RB1, and TMPRRSS2-ERG rearrangement of the original resected tumors. Some differences were seen in lines derived from several metastases of the same patient. These characteristics were maintained throughout the prolonged growth of >100 passages to date. Transcriptome analysis of LuCaP tumors over selected passages (p) - p40-p59 for AR− LuCaP 49, p64-p99 for AR+ LuCaP 35 - showed no detectable changes in overall gene expression []. Against the CSC core postulate, all prostate cancer cell types can initiate growth in mice rather than just CSC. Importantly, each LuCaP line, AR+ or AR−, retained its unique identity with no other cell types emerging over time. We suggest that this approach of generating multiple PDX could be replicated for other solid tumor types.

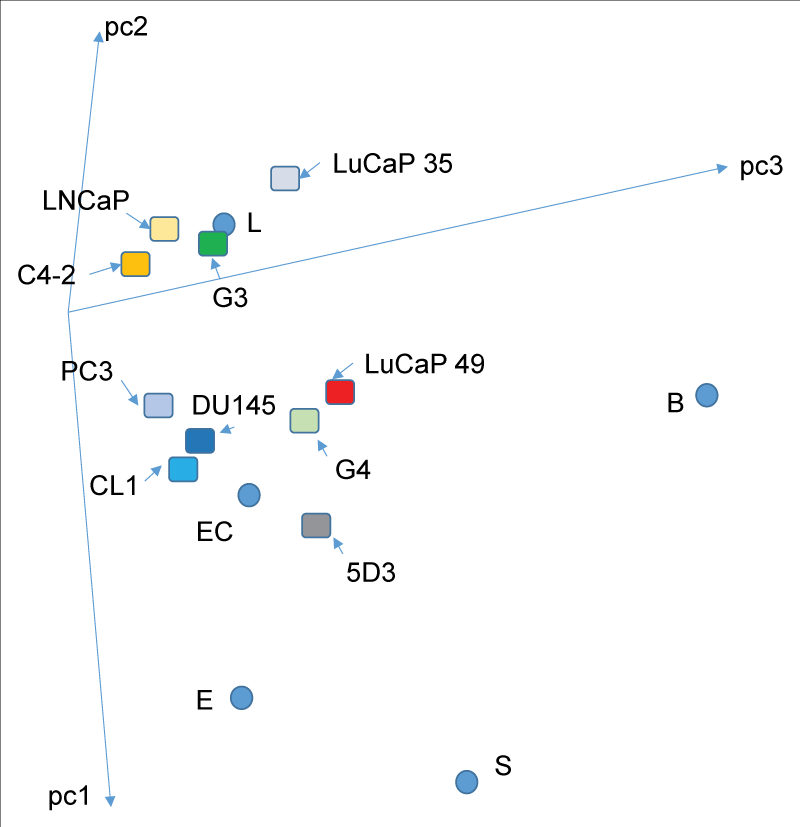

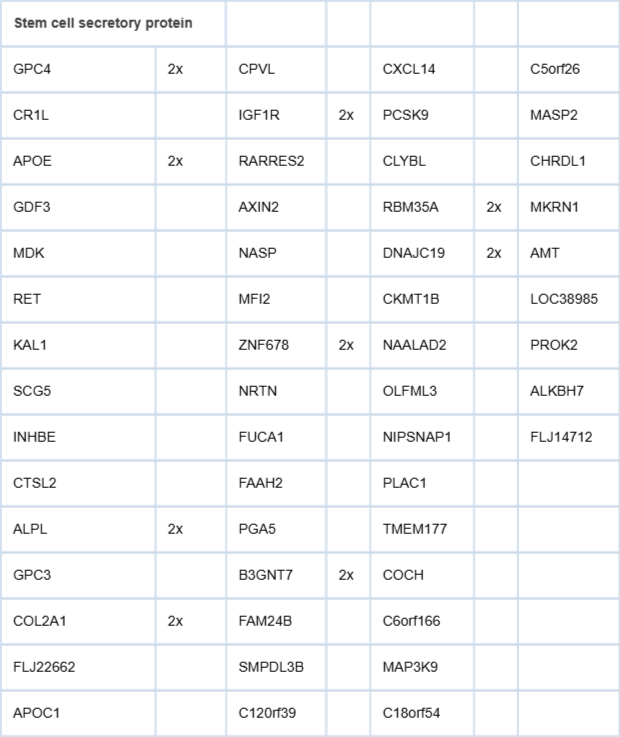

As described above, CD44 was used to identify breast cancer CSC, and has also been used as a distinguishing marker in pancreatic, colorectal, head and neck cancers [-]. CD44+ PC3 prostate cancer cells grown as xenografts were found to be enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic capabilities []. We generated a prostate CD map by immunohistochemistry using the CD antibodies available commercially [,]. For those associated with CSC, CD24, CD34, CD38, CD44, and CD133 all showed differential expression between normal/benign and cancer, as well as among cancer cells in culture. CD24 showed increased expression by cancer cells from low to high grade [,]. CD34 was detected mainly in infiltrating white blood cells. CD38 showed decreased expression in cancer cells. CD44 expression was restricted to basal epithelial cells and a few cancer cell lines []. Notably, the expression level of CD44 was not appreciably high in stem cells []. Transcriptome dataset query showed a >50-fold lower expression in embryonic stem (ES), embryonal carcinoma (EC), induced pluripotent (iPS) cells, and small cell carcinoma line LuCP49 than cancer cell lines DU145, PC3, and CL1 []. CD133 expression was detected in stem-like cancer cells but not in those of primary tumors []. The generated CD map allowed CD antibody-mediated sorting of prostate cell types - CD26+ luminal (L), CD104+ basal (B), CD49a+ stromal (S), plus CD31+ endothelial (E) for transcriptomics and cell-to-cell interaction analysis []. Together with those of ES, EC, and iPS, a prostate principal components analysis (PCA) space was generated to visualize cellular differentiation keyed on gene expression []. As expected, the four differentiated cell types, L, B, S, and E, were distinct in gene expression to reflect their own functional property. Their individual placements in the PCA space were widely separated on the periphery of the centrally placed stem cell types ES, EC, and iPS (Figure 1).

The separation between any two cell types represented by their respective transcriptome datapoints, measurable by a value Δ [,], corresponds to the degree of differential gene expression, and thus lineage relatedness. The PCA plot provides a visual tool to track cellular differentiation. The transcriptome of CD44+ basal cells, like those of the other differentiated cell types, was distal to that of the stem cells, hence not like stem cells. When the transcriptome datapoints of prostate cancer cell types (including CD44+ PC3, DU145, and CL1) were displayed in PCA (Figure 1), none were close to the basal cell datapoint. One can conclude that CD44 is not a particularly consistent marker associated with prostate cancer cells. Parenthetically, CD104+ basal cells of the bladder urothelium were also shown to possess no stem cell gene signature, and their gene expression was different from that of prostate basal cells, hence functionally distinct in the two organs []. Overall, the distribution of cancer cell datapoints revealed two separate groupings: either luminal-like around the L datapoint or less luminal-like, more stem-like around the ES, EC, and iPS datapoints. Included in this PCA display was the datapoint for a small CD44+ subpopulation (<1%) in the basal epithelium sortable by side population (SP) flow cytometry of cells capable of excluding Hoechst 33342 dye [], or antibody to ABCG2, the stem cell membrane pump responsible for dye efflux. These cells were first selected by CD44 to exclude CD31+ABCG2+CD44− endothelial cells []. Of note, CD31+ endothelial cells were also positive for CD133, hence not exclusively a stem cell marker [,]. The placement of the ABCG2+ cell datapoint near those of stem cells suggested a possibility of their representing an organ progenitor population []. Some cancer cells might derive from these CD44+ABCG2+ cells such as the CD44+ cell lines PC3, DU145, CL1. CL1 was, however, derived from the CD44− luminal-like LNCaP via growth in androgen-free media [,].

Figure 1: Prostate cancer cell types. In the PCA space, transcriptomes of the cancer cell types are displayed. One grouping is around the luminal cell datapoint (L) – LNCaP, C4-2, LuCaP 35 and G3. The other grouping is around the stem cell datapoint (EC) – PC3, DU145, CL1, LuCaP 49 and G4. 5D3 represents a possible prostate progenitor cell population sorted by antibody to ABCG2. No cancer cell type is close to the basal cell datapoint (B) even for the CD44+ PC3 or CL1. C4-2 and CL1 are derivatives of LNCaP through growth without androgen. The lines labeled pc1, pc2 and pc3 are the principal components axes of the 3D plot (adapted from ref. 7).

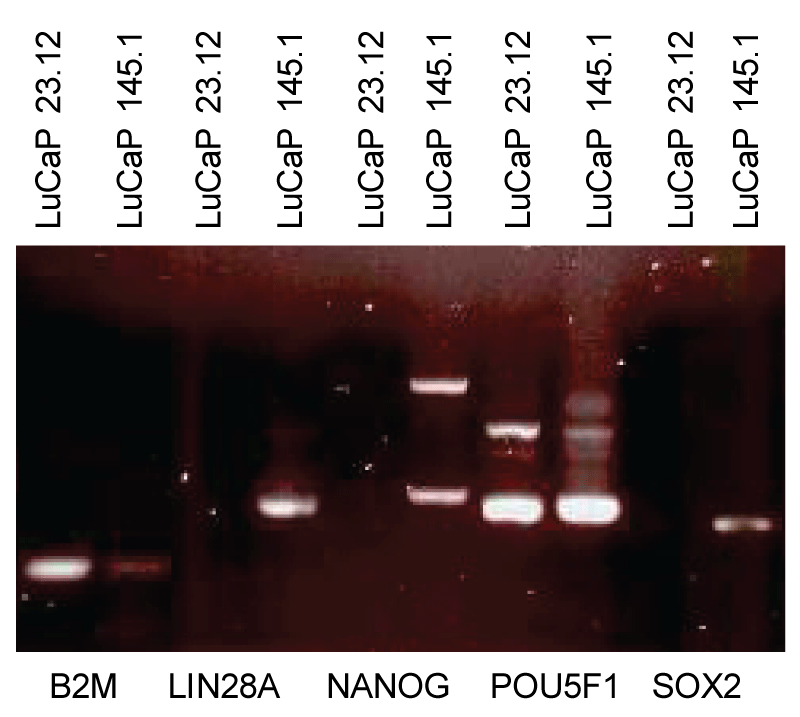

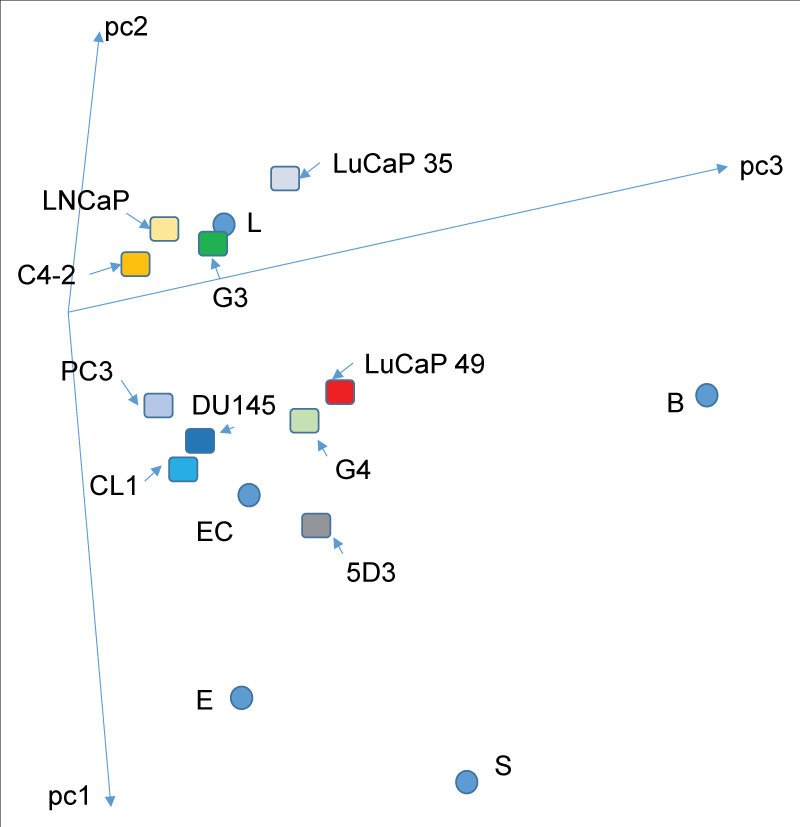

Figure 1: Prostate cancer cell types. In the PCA space, transcriptomes of the cancer cell types are displayed. One grouping is around the luminal cell datapoint (L) – LNCaP, C4-2, LuCaP 35 and G3. The other grouping is around the stem cell datapoint (EC) – PC3, DU145, CL1, LuCaP 49 and G4. 5D3 represents a possible prostate progenitor cell population sorted by antibody to ABCG2. No cancer cell type is close to the basal cell datapoint (B) even for the CD44+ PC3 or CL1. C4-2 and CL1 are derivatives of LNCaP through growth without androgen. The lines labeled pc1, pc2 and pc3 are the principal components axes of the 3D plot (adapted from ref. 7).Given that markers like CD44 are not specific to stem cells, what makes CSC stem-like? Transcriptomics has distinguished luminal-like adenocarcinoma vs. more stem-like non-adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma. A majority of the LuCaP PDX lines are luminal-like based on transcriptome, even though many of them were established from metastatic lesions of advanced diseases. For example, LuCaP 35 from a distant lymph node metastasis is more luminal-like than Gleason pattern 4 (G4) cancer cells of histologically non-glandular primary tumors. The basis that small cell carcinoma cells are stem-like is their expression of stem cell transcription factors (scTF) LIN28A, NANOG, POU5F1, and SOX2. This quartet of scTF could be used to convert adult cells into iPS cells with a resultant transcriptome like that of ES cells [,]. Figure 2 shows the presence of these scTF transcripts in small cell carcinoma LuCaP 145.1 vs. adenocarcinoma LuCaP 23.12. Of the four, only POU5F1 was present in LuCaP 23.12. SOX2 expression is likely responsible for the neuroendocrine phenotype of small cell carcinoma, as SOX2 can singly convert fibroblasts to induced neuronal stem cells []. Neuroendocrine genes, chromogranin A, enolase, and AURKA were also found in stem cells. The absence of stem cell RB1 in small cell carcinoma was a notable difference []. SOX2 was the sole scTF of four expressed by small cell carcinoma LuCaP 49 []. These scTFs were found expressed by other small cell carcinoma lines, LuCaP 93, LuCaP 145.2, non-adenocarcinoma lines, LuCaP 173.1, and LuCaP 173.2A []. LuCaP 77 showed expression of POU5F1 and LIN28A. The conversion from LuCaP 73 to LuCaP 73CR showed increased expression of LIN28A []. It is possible that scTF genes are activated sequentially in the progression from adenocarcinoma to non-adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma, as suggested by their expression levels in these different LuCaP cells [,]. Nevertheless, no scTF was detected in the transcriptomes of Gleason pattern 3 (G3) and G4 tumor cells []. CD133− adenocarcinoma cells showed signals for differentiation-associated AR, KLK3 (PSA), +/−CD10 (MME) but absent in CD133+ small cell carcinoma cells []. Significant is the differential expression levels of β-2 microglobulin (B2M), where it was found at a 10-fold lower level in stem cells (ES, EC, iPS), LuCaP 145.1 than differentiated G3 cancer cells, adenocarcinoma LuCaP 35, stromal cells of normal prostate (NPstrom) and stromal cells associated with cancer (CPstrom) through transcriptome dataset query of DNA microarray signal intensity values []. In a sense, stem and non-stem cells can be operationally phenotyped as scTF+B2Mlo and scTF−B2Mhi, respectively.

Figure 2: Stem cell factor expression in prostate cancer cells. Small cell carcinoma LuCaP 145.1 expresses LIN28A, NANOG, POU5F1 and SOX2, a low level of B2M, thus the phenotype of scTFB2Mlo. Adenocarcinoma LuCaP 23.12 expresses only POU5F1 and a higher level of B2M, thus the phenotype of scTFB2Mhi.

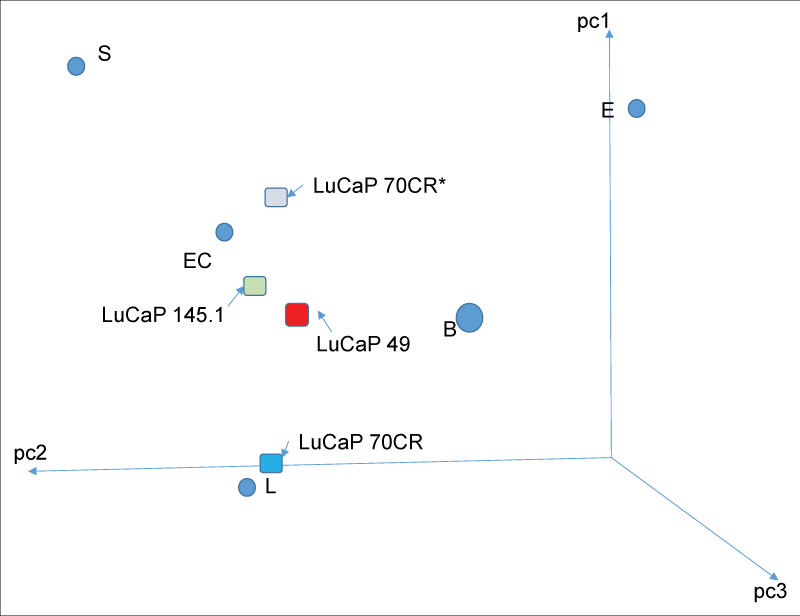

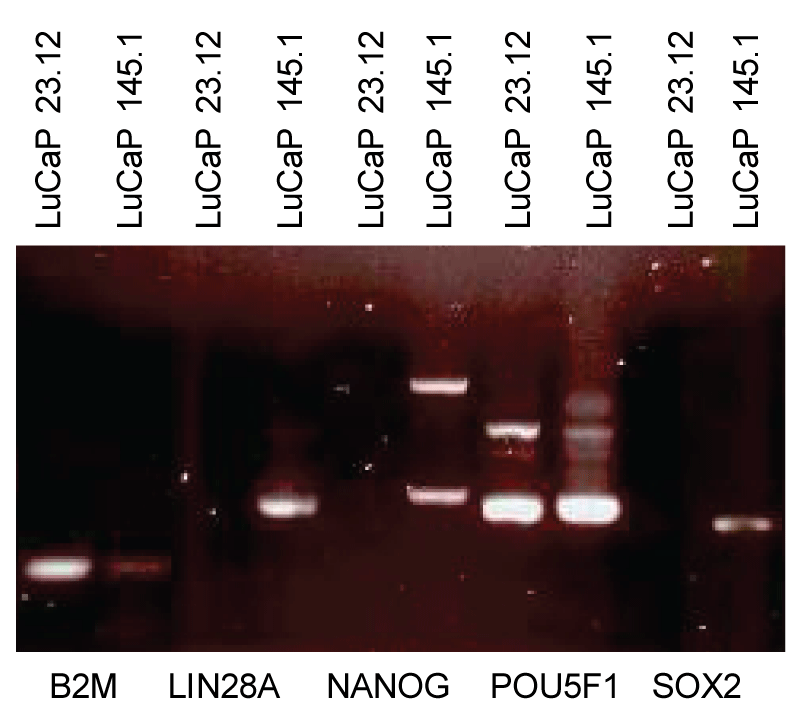

Figure 2: Stem cell factor expression in prostate cancer cells. Small cell carcinoma LuCaP 145.1 expresses LIN28A, NANOG, POU5F1 and SOX2, a low level of B2M, thus the phenotype of scTFB2Mlo. Adenocarcinoma LuCaP 23.12 expresses only POU5F1 and a higher level of B2M, thus the phenotype of scTFB2Mhi. Is the expression of scTF responsible for CSC? The presence of prostate cancer-specific TMPRSS2-ERG fusion in both adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the same tumor cases provides an argument for a direct lineage between the two tumor types []. Cases under active surveillance have been reported to show disease progression with adverse pathology, from a glandular to non-glandular histology with diminution or loss of luminal secretion []. Prostate cancer, like cancer in general, exhibits dedifferentiation in progression from lower to higher grades. Could scTF activation convert differentiated adenocarcinoma cells into undifferentiated small cell carcinoma cells? A few LuCaP xenograft lines could be forced to grow in vitro, but a majority could not. A method used in propagating ES and iPS cells in vitro was found to be applicable in adapting LuCaP lines to grow in culture [,]. This involves placing freshly prepared single LuCaP cells by collagenase digestion of minced tumor pieces in the presence of irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF). MEF can be harvested directly from mouse embryos or obtained from commercial vendors. In this way, LuCaP cells proliferate, can be passaged by trypsin treatment, and replated on MEF (irradiated MEF cannot be passaged). The in vitro grown LuCaP cells can be stored frozen in liquid N2 using a cooling protocol used in stem cell research []. The AR+ adenocarcinoma LuCaP 70CR, LuCaP 73CR, LuCaP 86.2, LuCaP 92, LuCaP 105CR were infected by lentiviral vectors containing LIN28A, NANOG, POU5F1, SOX2 gene cassettes []. In three weeks, the culture morphology changed, in which small, darker appearing (under light microscopy) cells took over, which differed from that of mock-infected cells. This cell appearance resembled that of cultured non-adenocarcinoma PC3 cells. Transcriptome analysis of LuCaP 70CR* [* to denote reprogrammed or induced pluripotent cancer (iPC) cells] showed a large difference with that of parental LuCaP 70CR (Figure 3). Our PCA software allows new transcriptome datasets to be displayed with respect to those of CD26+ luminal, CD49a+ stromal, CD104+ basal, CD31+ endothelial, ES, EC, iPS and others for lineage relationship. In LuCaP 70CR*, genes associated with differentiation, such as anterior gradient 2 (AGR2), PSA/KLK3, were down-regulated, as well as B2M. Signal values for LIN28A, NANOG, POU5F1, and SOX2 were increased. The value between the datapoints LuCaP 70CR* and LuCaP 70CR was 91.72, comparable to that between CPstrom and its derived iPS cells (NPstrom cells are refractory to reprogramming for the reason given below) []. Placement of the LuCaP 70CR* datapoint was distal to those of all the prostate cell types included, and separate from those of stem cells. LuCaP 70CR* was closest to LuCaP 145.1 (∆ = 45.85; compared to ∆ = 61.83 with EC, ∆ = 78.04 with ES). Also shown are the small cell carcinoma LuCaP 145.1 and LuCaP 49 with gene expression difference of ∆ = 58.95, which reflected the existence of subtypes as found in clinical specimens []. This measure was similar to ∆ = 41.42 between adenocarcinoma LuCaP 70CR and LuCaP 35. The reprogramming of differentiated cancer cells demonstrated that scTF were involved in prostate cancer dedifferentiation, and that adenocarcinoma could be converted to small cell carcinoma-like and stem-like with attendant changes in culture morphology and cell appearance, plus down-regulation of B2M. Since these initial experiments, scTF plasmid vectors of lower biosafety concern were generated that produced equivalent efficiency in reprogramming []. These vectors can be readily produced in large quantities rather than by the complicated route in preparing lentiviral vectors. Full-length scTF cDNA cloned from LuCaP 145.1 functioned as that cloned from ES cells to produce reprogrammed cells. Transfection of scTF into C4-2B, LNCaP, PC3, and human kidney fibroblasts HK293F produced stem-like derivatives with decreased B2M and culture morphology change; transfection with vectors containing other gene constructs did not []. Thus, scTF expression in adenocarcinoma leads to dedifferentiated cancer cells. The resultant stem-like cancer cells become less epithelial-like with loss of epithelial cell density (ρ = 1.07) to one of stromal cells (ρ = 1.035), shown by the banding of LuCaP 145.1 cells in a density gradient [,]. Association between expression of these four scTF and increased prostate cancer aggressiveness from adenocarcinoma to small cell carcinoma has been documented in the literature [-]. CSCs do exist in prostate cancer despite not identifiable by CD44 reactivity.

Figure 3: Reprogramming of adenocarcinoma LuCaP 70CR. The PCA display shows the gene expression change after transfection of scTF into LuCaP 70CR. The transcriptome datapoint of the resultant derivative, LuCaP 70CR*, is now localized to the stem-like grouping (adapted from ref. 25).

Figure 3: Reprogramming of adenocarcinoma LuCaP 70CR. The PCA display shows the gene expression change after transfection of scTF into LuCaP 70CR. The transcriptome datapoint of the resultant derivative, LuCaP 70CR*, is now localized to the stem-like grouping (adapted from ref. 25).Can prostate CSC undergo differentiation to produce other cancer cell types? In embryonic development of the prostate and bladder, the stromal mesenchyme controls the formation of these two organs. Organ stem or progenitor cells respond to stromal instruction by undergoing epithelial differentiation to produce prostate or bladder tissue accordingly []. This stromal induction is retained in the developed organs for tissue renewal and repair. By comparative transcriptomics between CD49a+ prostate stromal cells and CD13+ bladder stromal cells (localized adjacent to the basal urothelium), genes encoding secreted protein molecules were identified []. The experimental rationale was that these genes encode candidate organ-specific signaling hormone molecules. Among the identified were proenkephalin (PENK) specific to the prostate, stanniocalcins (STC1, SCT2) with differential expression in prostate vs. bladder. Bladder-specific secreted molecules were likewise identified. Prostate stromal expression of PENK was verified by immunohistochemistry using a polyclonal antibody generated via a selected peptide sequence. PENK was found to be a marker for also smooth muscle cells of the bladder muscularis and blood vessel walls. Prostate stromal cells are characterized as smooth muscle cells positive for actin (ACTA2), desmin (DES), caldesmon (CALD1), calponin (CNN1) [,]. Significantly, PENK was absent in CPstrom. One can conclude that this secreted molecule is no longer expressed by stromal cells associated with tumor cells. On the other hand, CPstrom differ from NPstrom by intense immunostaining for CD90, which was used to isolate these cells from tumor samples []. Transcriptomics showed the absence of PENK transcripts in CD90+ CPstrom []. Unlike PENK, STC1 was also expressed by luminal cells, but its transcript level was down-regulated in cancer cells and xenografts representing advanced diseases []. These results suggest that stromal influence through intercellular communication is either lost or diminished in tumors. Lack of differentiation signaling over time could lead to less differentiated and more stem-like cancer cells.

We designed a simple assay to test the functional property of stromal cells. Cultured CD49a+ NPstrom and CD13+ bladder stromal cells (NBstrom) or their respective cell-free conditioned media containing secreted molecules were added to an EC cell line, NCCIT, employed to serve as stem cells (ES cells were not allowed administratively for research) []. The stem cell marker alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was used to monitor the co-culture in a time course of 7 d. At selected time points, treated NCCIT cells were analyzed by DNA microarrays. In time, the colony morphology changed from that of stem cells to that of fibroblast-like with loss of ALP staining and decreased proliferation. In PCA, the transcriptome datapoints “migrated” from that of stem cells to cultured stromal cells (not sorted stromal cells due to proliferation genes activated when cells were placed in culture). Dataset query showed increases in the expression of NPstrom markers STC1, PENK, TNC, EDNRB, CNTN1, MMP3, verified by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). That the EC cells were induced to differentiate was evidenced by down-regulation of scTF and up-regulation of B2M. Plasticity in EC response was shown by co-culture with NBstrom. Down-regulation of scTF and up-regulation of B2M were similarly found but with increased expression of NBstrom genes such as GFRA1 and not that of NPstrom genes PENK, CNN1. The different levels of STC1 and STC2 between NPstrom and NBstrom were also replicated in the treated EC cells. In addition, CD90+PENK− CPstrom isolated from a G3 tumor induced down-regulation of scTF and up-regulation of B2M but without induction of PENK []. In essence, the stromal cells dictated how stem cells respond. Each response was specific to NPstrom, NBstrom or CPstrom. We postulate that such intercellular communication exists in every organ that requires tissue renewal. It remains to be studied for CPstrom isolated from G4 (nonglandular) or Gleason pattern 5 (G5, single cells) tumors as these sample types are now rarer especially in the era of robotic surgery. Since stem-like prostate cancer cells are scTF+B2Mlo could they also respond to stromal signaling trackable by down-regulation of scTF and up-regulation of B2M?

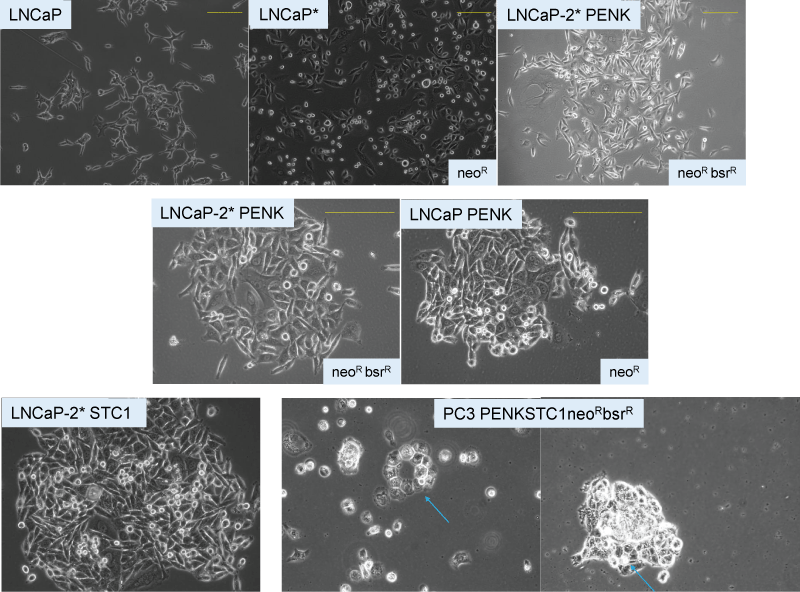

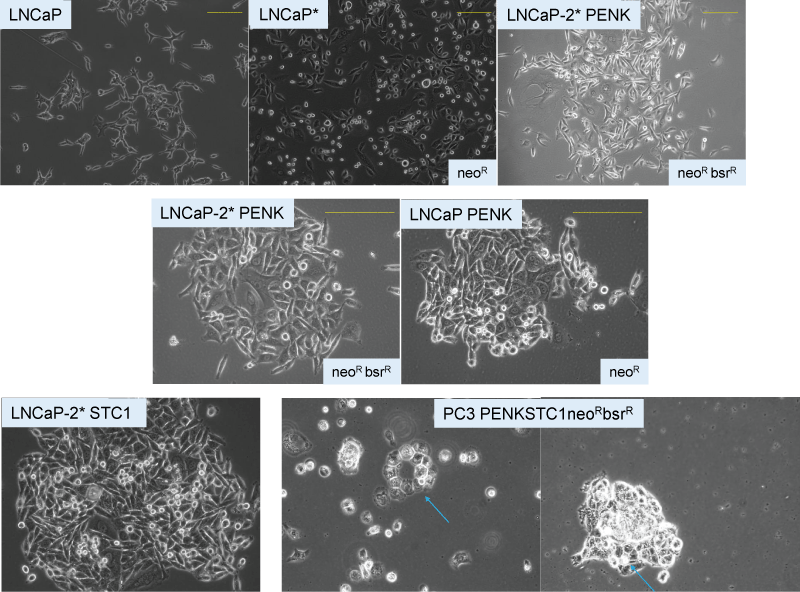

Small cell carcinoma LuCaP 145.1 adapted to in vitro growth was transfected by a plasmid vector containing the PENK gene cassette (pPENK1 vs. control vector). At 3 days, the cells were analyzed (a longer time course was not attempted because the MEF feeder cells were killed by the drug selection; without them, LuCaP cells could not survive) []. The RT-PCR result showed down-regulation of scTF and up-regulation of B2M to indicate that the LuCaP 145.1/PENK cells were undergoing differentiation. Of the four scTF monitored, expression of POU5F1 was less affected due to this factor being expressed by many LuCaP lines of adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma (cf. Figure 2). Moreover, differentiation through PENK and dedifferentiation through scTF can both take place in cancer cells. scTF−B2Mhi adenocarcinoma (AR+PSA+) LNCaP prostate cancer cells were first reprogrammed by scTF transfection using our constructed plasmids pLP4 (LIN28A-POU5F1)-neo and pSN2 (SOX2-NANOG)-neo [] to obtain neoRscTF+B2Mlo LNCaP*. The cell appearance was changed, as occurred with scTF reprogrammed LuCaP adenocarcinoma lines. One clone, LNCaP*-2, was then transfected with pPENK1-bcr. The resultant neoRbsrRLNCaP*-2/PENK cells lost the stem-like appearance, replaced by one resembling that of LNCaP transfected by pPENK (Figure 4). Thus, cancer cells can undergo dedifferentiation from scTF−B2Mhi to scTF+B2Mlo, and re-differentiation back to scTF−B2Mhi. These various phenotypes were maintained in serial passages as the plasmid sequences were incorporated into the genome. Thus, PENK can antagonize multiple stem cell transcription factors simultaneously. Being aneuploid with multiple known DNA mutations did not appear to hinder differentiation in LNCaP. One can perform a systematic investigation to see whether this applies to all the available prostate cancer cell lines or even cell lines of other tumor types. Since PENK acts on scTF, other tumor cell types with expression of scTF would also likely respond to PENK. For example, PENK could be tested on lung small cell cancer cells if they are shown to be stem-like with the scTF+B2Mlo phenotype. Furthermore, identified NBstrom signaling molecules could likewise induce stem-like prostate cancer cells to undergo differentiation, as shown by their effect on NCCIT. This would demonstrate that stem-like cancer cells also possess response plasticity of normal stem cells. We postulate that signaling molecules could be identified in all organs, and tumor progression in these organs would follow the pathway of dedifferentiation from an initial differentiated cancer phenotype to more stem-like phenotypes. The following research could be carried out to show whether the mouse equivalent of Penk has any effect on LuCaP 145.1; whether stem-like cancer cells can be induced to differentiate into pseudo-normal or non-prostatic cell types, depending on the signaling applied [-].

Figure 4: Prostate cancer cell dedifferentiation and differentiation. The top five panels show LNCaP, LNCaP+scTF=LNCaP-2*, LNCaP-2*+PENK. Gene expression changes as monitored by transcriptome analysis are accompanied by changes in cell appearance. The bottom three panels show LNCaP-2* transfected by STC1 and the more stem-like PC3 by PENK and STC1. Gland-like cell clusters (blue arrows) with a central lumen can be seen in PC3/PENKSTC1. neoR and bsrR indicate drug resistance in the selection of transfected cells.

Figure 4: Prostate cancer cell dedifferentiation and differentiation. The top five panels show LNCaP, LNCaP+scTF=LNCaP-2*, LNCaP-2*+PENK. Gene expression changes as monitored by transcriptome analysis are accompanied by changes in cell appearance. The bottom three panels show LNCaP-2* transfected by STC1 and the more stem-like PC3 by PENK and STC1. Gland-like cell clusters (blue arrows) with a central lumen can be seen in PC3/PENKSTC1. neoR and bsrR indicate drug resistance in the selection of transfected cells.Like PENK in the embryonic mesenchyme [,], the STC1 and STC2 proteins have a similar function in organ development. STC1 and STC2 regulate phosphate transport across the epithelia and promote cellular maturation [,]. STC1 was induced in NPstrom-treated NCCIT cells at an earlier point than PENK []. Unlike PENK, it is not silenced in primary prostate cancer with expression in both cancer epithelial and cancer-associated stromal cells []. Its expression was found to decrease in disease progression, with cancer cell and xenograft lines showing reduced levels []. The effect of PENK on prostate cancer cell morphology is shown above. The PENK-transfected LNCaP cells appeared in close contact with each other, unlike untransfected cells. A similar appearance change was seen when LNCaP cells were transfected with STC1 []. When both PENK and STC1 were transfected into the more stem-like PC3 cells, organoid-like cell clusters were obtained. A gland-like structure with cells around a central luminal space was found (Figure 4) []. A follow-up study could probe the synergistic effect of PENK + STC1 on a panel of LuCaP adenocarcinoma, non-adenocarcinoma, and small cell carcinoma lines, each with its unique genomic alterations. In addition, STC2 could be included using an expression plasmid gene copy number of 2:1 STC1:STC2 to mimic their stromal cell expression levels [,]. The transfections could start with STC1 and STC2, to be followed by PENK. Changes in cell shape are monitored for correspondence to the expression of tight junction proteins. These protein molecules, located between functional epithelial cells, provide apicobasal polarity for polarized secretion. Barrier integrity is maintained by transmembrane proteins such as claudins, occludins, and junctional adhesion molecules []. Abnormal expression of tight junction proteins can be found in different solid tumor types [,]. Loss of claudin is linked to castration-resistant prostate cancer []. Restoring the expression of claudin and others through PENK and STC could constitute a form of effective cancer differentiation treatment. The influence of all secreted stromal factors found in conditioned media could be tested, as was studied with NCCIT. Response plasticity of stem-like prostate cancer cells can be tested by using NBstrom and CPstrom; transcriptomics is used to identify differential gene expression in the resultant cells. An interesting experiment is to prepare CPstrom from G3 vs. G4 or G5 tumors for incubation with NCCIT, followed by adenocarcinoma and non-adenocarcinoma cells to determine the specific defects in mesenchymal-epithelial interaction of these tumor grades. Thus, prostate CSC can differentiate in response to secreted factors from stromal cells. Maintenance of gene expression over multiple passages in mice indicates that CSCs do not undergo spontaneous differentiation or are induced by host factors.

As alluded to above, is the aggressiveness of CSC attributed to accumulated mutations in the genome over the disease course? Exome sequencing showed no such pattern of a high number of DNA mutations for scTF+B2Mlo small cell carcinoma []. DNA mutations detected in the LuCaP lines studied presented the following order in decreasing numbers: adenocarcinomas LuCaP 58/liver metastasis > LuCaP 73/primary > LuCaP 147/node metastasis > small cell carcinoma LuCaP 145.2/node metastasis (a sister clone of LuCaP 145.1/liver metastasis). One hypermutated genome was found to contain ten times more single-nucleotide variations. No substantially different patterns of structural alterations, gain or loss in chromosome copy numbers, interchromosomal translocations, intrachromosomal rearrangements among tumors of similar grade and stage, presence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion were found. No trend of more changes with higher disease grade or stage was detected []. These findings contrast the mutational basis of carcinogenesis and one of the key features of the CSC postulate. Similar findings were found among types of breast cancer []. For small cell carcinoma of the bladder and lung, genomic changes were specific to the organ rather than to the cancer type []. The transition from urothelial carcinoma to small cell carcinoma also appeared to involve dedifferentiation. As described above, there are more gene expression changes between CPstrom and NPstrom than between G3 cancer and luminal epithelial cells, yet no significant mutations were detected in tumor-associated stromal cells []. In other words, there is no correlation between gene expression changes in cancer and the degree of genomic changes.

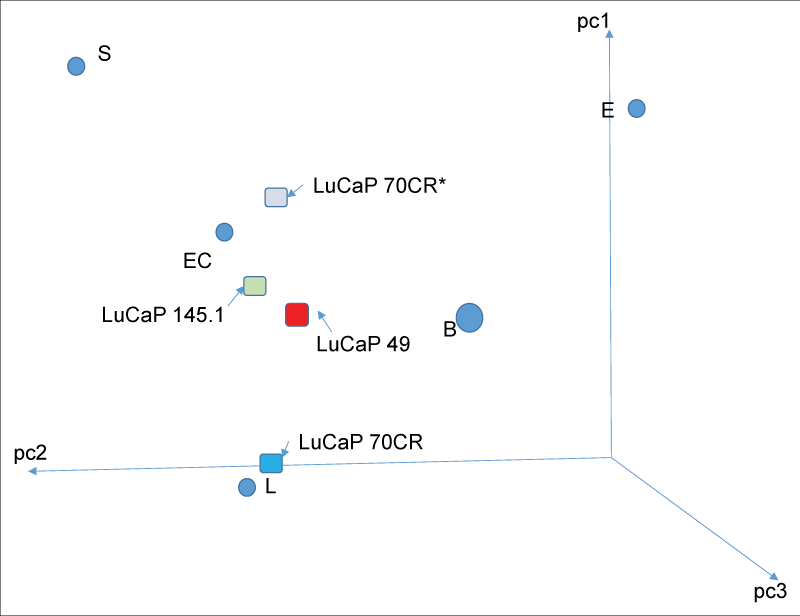

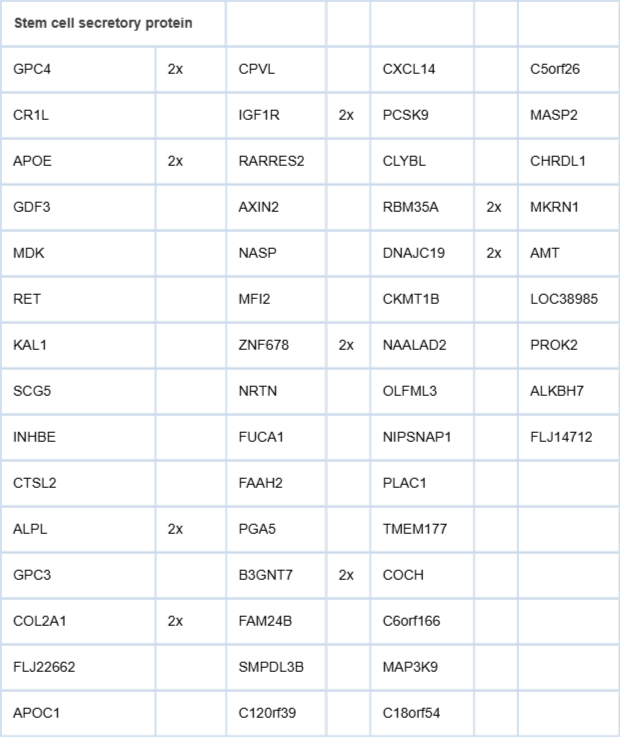

What is the lineage relationship between CPstrom and NPstrom? We found that the interaction between NPstrom and NCCIT was bidirectional. The effect of stem cell-secreted factors on stromal cells was monitored by transcriptomics. PCA of the transcriptome datasets showed that the datapoint of NPstrom+NCCIT “migrated” toward that of CPstrom. The change was also evident in the expression of microRNA (miRNA) []. mRNA transcripts of CD90, MiRN21, HGF, SFRP1, and BGN were increased in correspondence with their higher levels in CPstrom. HGF, a mediator of stromal-epithelial interaction, is expressed by undifferentiated mesenchyme in embryogenesis []. Increased miRNA species included miR-21 (processed from MiRN21), let-7f, miR-23a, miR29b. miR-21 is associated with dedifferentiation []. On the other hand, NCCIT factors showed minimal effect on CPstrom (datapoints CPstrom+NCCIT=CPstrom). Table 1 lists the candidate genes encoding secreted proteins from NCCIT for converting NPstrom to CPstrom. As a result, a less differentiated stroma could be the underlying cause for the emergence of cancer cells. One research approach could employ partitioning of NCCIT conditioned media into molecular weight fractions, each of which are added to NPstrom to narrow down the pool of candidates. Thus, by total gene expression, CPstrom represents an under-differentiated version of NPstrom missing PENK and other possibly key signaling molecules to instruct epithelial maturation. Of note, due to the antagonistic effect of PENK on scTF PENK-positive NPstrom could not be reprogrammed whereas PENK-negative CPstrom could [].

Table 1: Stem cell secreted proteins. Listed are genes encoding proteins secreted by NCCIT in culture. “2x” indicates higher expression than the others according to DNA microarray signal intensity values.

Table 1: Stem cell secreted proteins. Listed are genes encoding proteins secreted by NCCIT in culture. “2x” indicates higher expression than the others according to DNA microarray signal intensity values.As NPstrom is being replaced by CPstrom in tumor foci, NPstrom in the non-involved part of the gland is being ablated by cancer-secreted AGR2. Secreted Agr2 in lower vertebrates is involved in limb regeneration []. Receptor binding in wound tissue initiates removal of cells and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells. In prostate cancer, the secreted AGR2 affects NPstrom through induction of programmed cell death (PCD) [], thus depleting further functional stromal signaling. As a consequence, epithelial differentiation is compromised leading to less luminal-like more stem-like abnormal cells over time. Down-regulation of STC1 in cancer cells may also be a contributing factor. Further research will attempt to better understand prostate cellular differentiation, how PENK and STC proteins function in concert, and how their genes are activated.

The AGR2 protein exists in two forms: intracellular iAGR2 and extracellular eAGR2. In normal cells, the form is iAGR2 localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, while in cancer cells, overexpression leads to a portion being secreted and localized to the cell surface, hence eAGR2 [,]. In prostate cancer, the specific phenotype of AGR2hiCD10lo has a 9-fold survival advantage over that of AGR2loCD10hi []. CD10 functions in allowing escape of cancer cells from the glandular capsule, as cancer cells in a majority of local metastases are CD10hiAGR2−/lo [,]. In addition, AGR2 expression is associated with cancer differentiation, and transcriptomes of AGR2hi cancer cells like LNCaP, LuCaP 35, established from lymph node metastases show them to be luminal-like []. However, immunostaining showed that most distant metastases in bone, lung, and liver had high expression of AGR2 (and low expression of CD10) []. LuCaP lines established from these lesions are luminal-like, not more stem-like, as one would expect if metastatic capability is restricted to CSC []. For extracapsular cancer cells, AGR2 is needed for dissemination throughout the body. In the absence of androgen in culture, CD10+AGR2− LNCaP was converted to more stem-like CD10−AGR2+ CL1 (cf. Figure 1) [], and this derivative acquired metastatic capability []. Dormancy in prostate cancer, in which recurrence occurs after a latent period post-treatment [,] may be explained by the need for a gene expression change from AGR2−/lo to AGR+ in tumor cells. These dormant cancer cells were PSA+ (i.e., differentiated) as RT-PCR of PSA was used to detect them. Other results showed that benign non-metastatic rat mammary tumor cells transfected by human AGR2 produced lung metastasis in syngeneic hosts []. Inhibition of AGR2 in mouse models could prevent cancer metastasis []. Part of the metastatic process may involve cancer-secreted AGR2 to induce PCD of susceptible cells, allowing colonization of migrating cancer cells in their place. In contrast, small cell carcinoma lesions in metastases and the LuCaP lines established from them were not stained for AGR2 []. Acquisition of stem-like characteristics (AGR2−CD10−scTF+B2Mlo) is not a requisite for dissemination. At present, we lack experimental proof that AGR2-negative small cell carcinoma cannot metastasize. In general, AGR2+ tumor cells are found in many solid tumor types []. A cohort of 12,434 tumors from 134 categories was immunostained, with the result that a majority were positive for AGR2. Non-epithelial neoplasms rarely showed expression. Besides prostate, the cases probed were female genital tract adenocarcinoma, breast cancer subtypes, adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract, pancreatic cancer, lung cancer, and urothelial carcinoma. Since eAGR2 is cancer-specific, curative treatment and a cancer vaccine based on targeting eAGR2 could be envisaged, especially since non-cancer cells express iAGR2 in the cell interior and are therefore invisible to anti-AGR2 antibodies []. Thus, AGR2 expression can be switched on and off during the prostate cancer disease course. The involvement of AGR2 and CD10 in metastatic spread of prostate cancer, bladder cancer, and lung cancer is complex and entails interaction with different other proteins, as detailed previously []. Like AGR2 in cancer, CD10 can exist in two forms - intracellular iCD10 [], where it interacts with heat shock proteins in the cytoplasm [], and extracellular eCD10, the common form of normal cells.

We postulate that cancer in the prostate arises as a result of defective epithelial differentiation. The tissue renewal process is controlled by CD49a+ stromal smooth muscle cells through, in part, signaling molecules such as PENK and STC [,]. The defect occurs when smooth muscle cell differentiation is arrested at an earlier stage, as represented by CD90 CPstrom. These cells fail to synthesize PENK, among others. Without it, the maturation of epithelial cells is stalled. The resultant neoplastic cells overexpress AGR2, [] and cancer-secreted AGR2 further depletes functional stromal cells through PCD. As the disease progresses, the tumor epithelial cells begin to lose expression of STC1 (and STC2) and perhaps other genes associated with differentiation [], eventually becoming stem-like. Reprogramming of adenocarcinoma to stem-like small cell carcinoma-like indicates that scTF could be reactivated in the absence of differentiation, or not inactivated in developing epithelial cells without STC1 and PENK. Forced expression of STC1 and PENK in cancer cells could produce organized glandular structures.

Successful mouse implantation to establish the family of LuCaP lines contradicts the supposition that only stem-like human tumors could initiate growth in vivo. All established tumor types can be maintained over multiple passages without detectable changes in gene expression and individual growth characteristics. This shows that stem-like cancer cells do not undergo differentiation spontaneously to yield non-stem-like progenies. Rather, stem-like cancer cells respond to hormone molecules secreted by stromal cells with down-regulation of scTF and up-regulation of B2M, with attendant changes in cell shape. This response is indifferent to the background levels of DNA mutations or aneuploidy in the tumor cells. Prostate cancer cells can readily undergo differentiation and dedifferentiation, suggesting that disease progression could be reversed.

Prostate cancer metastasis consists of two separate phases. First, CD10 is responsible for extracapsular escape. This is reflected in the association of poor patient outcome with CD10 expression in tumor cells. Second, AGR2 is needed for the spread throughout the body. This is manifested by the presence of luminal-like AGR2-positive instead of strictly stem-like tumor cells in distant metastases. Acquisition of stemness is, therefore, not a precondition for cancer spread. Emergence of stem-like cancer cells is due to suppression of differentiation through absence of signaling. Application of anti-androgen in treatment provides supporting evidence since testosterone is required for differentiation of this hormone-dependent organ []. This biology of prostate cancer differentiation could be equally applicable to describe other solid tumor types, in particular breast cancer in another hormone-dependent organ []. The proper signaling molecules await identification. Research effort could be spent on establishing multiple breast cancer xenografts [] using the methodology developed in the establishment of LuCaP lines. We will use the experimental procedures to study the identified bladder stromal factors on urothelial cell differentiation. In summary, our work in prostate cancer has shown that CSC exist, and that their stem-like characteristics are due to dedifferentiation/re-activation of scTF or arrested differentiation because of faulty intercellular communication. Accumulation of DNA mutations and acquisition of metastatic capability are not specific to CSC. The reliance of mouse implantation and certain markers to define CSC (more appropriately, stem-like cancer cells) is problematic.

Tan BT, Park CY, Ailles LE, Weissman IL. The cancer stem cell hypothesis: a work in progress. Lab Invest. 2006 Dec;86(12):1203-7. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700488. Epub 2006 Oct 30. PMID: 17075578.

Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997 Jul;3(7):730-7. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. PMID: 9212098.

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Apr 1;100(7):3983-8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. Epub 2003 Mar 10. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 May 27;100(11):6890. PMID: 12629218; PMCID: PMC153034.

Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003 Sep 15;63(18):5821-8. PMID: 14522905.

Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, Bronner-Fraser M, Kornblum HI. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Dec 9;100(25):15178-83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. Epub 2003 Nov 26. PMID: 14645703; PMCID: PMC299944.

Nguyen HM, Vessella RL, Morrissey C, Brown LG, Coleman IM, Higano CS, Mostaghel EA, Zhang X, True LD, Lam HM, Roudier M, Lange PH, Nelson PS, Corey E. LuCaP Prostate Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts Reflect the Molecular Heterogeneity of Advanced Disease an--d Serve as Models for Evaluating Cancer Therapeutics. Prostate. 2017 May;77(6):654-671. doi: 10.1002/pros.23313. Epub 2017 Feb 3. PMID: 28156002; PMCID: PMC5354949.

Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Vessella RL, Ware CB, Vêncio EF, Denyer G, Liu AY. Lineage relationship of prostate cancer cell types based on gene expression. BMC Med Genomics. 2011 May 23;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-46. PMID: 21605402; PMCID: PMC3113924.

Lee CJ, Dosch J, Simeone DM. Pancreatic cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jun 10;26(17):2806-12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6702. PMID: 18539958.

Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, Liu R, Wang X, Cho RW, Hoey T, Gurney A, Huang EH, Simeone DM, Shelton AA, Parmiani G, Castelli C, Clarke MF. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jun 12;104(24):10158-63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. Epub 2007 Jun 4. PMID: 17548814; PMCID: PMC1891215.

Mallika L, Rajarathinam M, Thangavel S. Cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its associated markers: A review. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2024 Apr 1;67(2):250-258. doi: 10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_467_23. Epub 2023 Nov 9. PMID: 38394427.

Patrawala L, Calhoun T, Schneider-Broussard R, Li H, Bhatia B, Tang S, Reilly JG, Chandra D, Zhou J, Claypool K, Coghlan L, Tang DG. Highly purified CD44+ prostate cancer cells from xenograft human tumors are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic progenitor cells. Oncogene. 2006 Mar 16;25(12):1696-708. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209327. PMID: 16449977.

Liu AY, True LD. Characterization of prostate cell types by CD cell surface molecules. Am J Pathol. 2002 Jan;160(1):37-43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64346-5. PMID: 11786396; PMCID: PMC1867111.

Liu AY, Roudier MP, True LD. Heterogeneity in primary and metastatic prostate cancer as defined by cell surface CD profile. Am J Pathol. 2004 Nov;165(5):1543-56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63412-8. PMID: 15509525; PMCID: PMC1618667.

Quek SI, Ho ME, Loprieno MA, Ellis WJ, Elliott N, Liu AY. A multiplex assay to measure RNA transcripts of prostate cancer in urine. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045656. Epub 2012 Sep 20. PMID: 23029164; PMCID: PMC3447789.

Liu AY. Differential expression of cell surface molecules in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000 Jul 1;60(13):3429-34. PMID: 10910052.

Oudes AJ, Campbell DS, Sorensen CM, Walashek LS, True LD, Liu AY. Transcriptomes of human prostate cells. BMC Genomics. 2006 Apr 25;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-92. PMID: 16638148; PMCID: PMC1553448.

Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Goo YA, Page LS, Shadle CP, Liu AY. Temporal expression profiling of the effects of secreted factors from prostate stromal cells on embryonal carcinoma stem cells. Prostate. 2009 Sep 1;69(12):1353-65. doi: 10.1002/pros.20982. PMID: 19455603.

Vêncio RZ, Koide T. HTself: self-self based statistical test for low replication microarray studies. DNA Res. 2005;12(3):211-4. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi007. PMID: 16303752.

Liu AY, Vêncio RZ, Page LS, Ho ME, Loprieno MA, True LD. Bladder expression of CD cell surface antigens and cell-type-specific transcriptomes. Cell Tissue Res. 2012 Jun;348(3):589-600. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1383-y. Epub 2012 Mar 20. PMID: 22427119; PMCID: PMC3367057.

Pascal LE, Oudes AJ, Petersen TW, Goo YA, Walashek LS, True LD, Liu AY. Molecular and cellular characterization of ABCG2 in the prostate. BMC Urol. 2007 Apr 10;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-7-6. PMID: 17425799; PMCID: PMC1853103.

Hirschmann-Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG, Nuchtern JG, Jax TW, Gobel U, Goodell MA, Brenner MK. A distinct "side population" of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Sep 28;101(39):14228-33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400067101. Epub 2004 Sep 20. PMID: 15381773; PMCID: PMC521140.

Patel BJ, Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Tsui KH, Paik SH, Caliliw R, Sheriff S, Wu L, deKernion JB, Tso CL, Belldegrun AS. CL1-GFP: an androgen independent metastatic tumor model for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000 Oct;164(4):1420-5. PMID: 10992426.

Liu AY, Brubaker KD, Goo YA, Quinn JE, Kral S, Sorensen CM, Vessella RL, Belldegrun AS, Hood LE. Lineage relationship between LNCaP and LNCaP-derived prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2004 Jul 1;60(2):98-108. doi: 10.1002/pros.20031. PMID: 15162376.

Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007 Dec 21;318(5858):1917-20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. Epub 2007 Nov 20. PMID: 18029452.

Vêncio EF, Nelson AM, Cavanaugh C, Ware CB, Milller DG, Garcia JC, Vêncio RZ, Loprieno MA, Liu AY. Reprogramming of prostate cancer-associated stromal cells to embryonic stem-like. Prostate. 2012 Sep 15;72(13):1453-63. doi: 10.1002/pros.22497. Epub 2012 Feb 7. PMID: 22314551.

Ring KL, Tong LM, Balestra ME, Javier R, Andrews-Zwilling Y, Li G, Walker D, Zhang WR, Kreitzer AC, Huang Y. Direct reprogramming of mouse and human fibroblasts into multipotent neural stem cells with a single factor. Cell Stem Cell. 2012 Jul 6;11(1):100-9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.018. Epub 2012 Jun 7. PMID: 22683203; PMCID: PMC3399516.

Borges GT, Vêncio EF, Quek SI, Chen A, Salvanha DM, Vêncio RZ, Nguyen HM, Vessella RL, Cavanaugh C, Ware CB, Troisch P, Liu AY. Conversion of Prostate Adenocarcinoma to Small Cell Carcinoma-Like by Reprogramming. J Cell Physiol. 2016 Sep;231(9):2040-7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25313. Epub 2016 Feb 4. PMID: 26773436.

Kanan AD, Corey E, Vêncio RZN, Ishwar A, Liu AY. Lineage relationship between prostate adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2019 May 30;19(1):518. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5680-7. PMID: 31146720; PMCID: PMC6543672.

Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Page LS, Liebeskind ES, Shadle CP, Troisch P, Marzolf B, True LD, Hood LE, Liu AY. Gene expression relationship between prostate cancer cells of Gleason 3, 4 and normal epithelial cells as revealed by cell type-specific transcriptomes. BMC Cancer. 2009 Dec 18;9:452. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-452. PMID: 20021671; PMCID: PMC2809079.

Williamson SR, Zhang S, Yao JL, Huang J, Lopez-Beltran A, Shen S, Osunkoya AO, MacLennan GT, Montironi R, Cheng L. ERG-TMPRSS2 rearrangement is shared by concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and prostatic small cell carcinoma and absent in small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: evidence supporting monoclonal origin. Mod Pathol. 2011 Aug;24(8):1120-7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.56. Epub 2011 Apr 15. PMID: 21499238; PMCID: PMC3441178.

Newcomb LF, Thompson IM Jr, Boyer HD, Brooks JD, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR, Dash A, Ellis WJ, Fazli L, Feng Z, Gleave ME, Kunju P, Lance RS, McKenney JK, Meng MV, Nicolas MM, Sanda MG, Simko J, So A, Tretiakova MS, Troyer DA, True LD, Vakar-Lopez F, Virgin J, Wagner AA, Wei JT, Zheng Y, Nelson PS, Lin DW; Canary PASS Investigators. Outcomes of Active Surveillance for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer in the Prospective, Multi-Institutional Canary PASS Cohort. J Urol. 2016 Feb;195(2):313-20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.087. Epub 2015 Aug 29. PMID: 26327354; PMCID: PMC4970462.

Liu AY. Prostate cancer research: tools, cell types, and molecular targets. Front Oncol. 2024 Mar 26;14:1321694. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1321694. PMID: 38595814; PMCID: PMC11002103.

Epstein JI, Amin MB, Beltran H, Lotan TL, Mosquera JM, Reuter VE, Robinson BD, Troncoso P, Rubin MA. Proposed morphologic classification of prostate cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014 Jun;38(6):756-67. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000208. PMID: 24705311; PMCID: PMC4112087.

Liu AY. The opposing action of stromal cell proenkephalin and stem cell transcription factors in prostate cancer differentiation. BMC Cancer. 2021 Dec 15;21(1):1335. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09090-y. PMID: 34911496; PMCID: PMC8675470.

Albino D, Civenni G, Dallavalle C, Roos M, Jahns H, Curti L, Rossi S, Pinton S, D'Ambrosio G, Sessa F, Hall J, Catapano CV, Carbone GM. Activation of the Lin28/let-7 Axis by Loss of ESE3/EHF Promotes a Tumorigenic and Stem-like Phenotype in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016 Jun 15;76(12):3629-43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2665. Epub 2016 May 2. PMID: 27197175.

Jeter CR, Liu B, Lu Y, Chao HP, Zhang D, Liu X, Chen X, Li Q, Rycaj K, Calhoun-Davis T, Yan L, Hu Q, Wang J, Shen J, Liu S, Tang DG. NANOG reprograms prostate cancer cells to castration resistance via dynamically repressing and engaging the AR/FOXA1 signaling axis. Cell Discov. 2016 Nov 15;2:16041. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2016.41. PMID: 27867534; PMCID: PMC5109294.

Kosaka T, Mikami S, Yoshimine S, Miyazaki Y, Daimon T, Kikuchi E, Miyajima A, Oya M. The prognostic significance of OCT4 expression in patients with prostate cancer. Hum Pathol. 2016 May;51:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.12.008. Epub 2015 Dec 30. PMID: 27067776.

Yu X, Cates JM, Morrissey C, You C, Grabowska MM, Zhang J, DeGraff DJ, Strand DW, Franco OE, Lin-Tsai O, Hayward SW, Matusik RJ. SOX2 expression in the developing, adult, as well as, diseased prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014 Dec;17(4):301-9. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.29. Epub 2014 Aug 5. PMID: 25091041; PMCID: PMC4227931.

Cunha GR. Urogenital development: a four-part story of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions. Differentiation. 2010 Sep-Oct;80(2-3):79-80. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.08.004. Epub 2010 Sep 1. PMID: 20813448; PMCID: PMC4699566.

Goo YA, Goodlett DR, Pascal LE, Worthington KD, Vessella RL, True LD, Liu AY. Stromal mesenchyme cell genes of the human prostate and bladder. BMC Urol. 2005 Dec 12;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-5-17. PMID: 16343351; PMCID: PMC1327674.

Di Carlo E, Sorrentino C. The multifaceted role of the stroma in the healthy prostate and prostate cancer. J Transl Med. 2024 Sep 5;22(1):825. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05564-2. PMID: 39238004; PMCID: PMC11378418.

Pascal LE, Goo YA, Vêncio RZ, Page LS, Chambers AA, Liebeskind ES, Takayama TK, True LD, Liu AY. Gene expression down-regulation in CD90+ prostate tumor-associated stromal cells involves potential organ-specific genes. BMC Cancer. 2009 Sep 8;9:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-317. PMID: 19737398; PMCID: PMC2745432.

True LD, Zhang H, Ye M, Huang CY, Nelson PS, von Haller PD, Tjoelker LW, Kim JS, Qian WJ, Smith RD, Ellis WJ, Liebeskind ES, Liu AY. CD90/THY1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts and could serve as a cancer biomarker. Mod Pathol. 2010 Oct;23(10):1346-56. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.122. Epub 2010 Jun 18. PMID: 20562849; PMCID: PMC2948633.

Pascal LE, Ai J, Vêncio RZ, Vêncio EF, Zhou Y, Page LS, True LD, Wang Z, Liu AY. Differential Inductive Signaling of CD90 Prostate Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Compared to Normal Tissue Stromal Mesenchyme Cells. Cancer Microenviron. 2011 Jan 7;4(1):51-9. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0061-4. PMID: 21505567; PMCID: PMC3047627.

Kumar A, White TA, MacKenzie AP, Clegg N, Lee C, Dumpit RF, Coleman I, Ng SB, Salipante SJ, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA, Corey E, Lange PH, Morrissey C, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Shendure J. Exome sequencing identifies a spectrum of mutation frequencies in advanced and lethal prostate cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Oct 11;108(41):17087-92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108745108. Epub 2011 Sep 26. PMID: 21949389; PMCID: PMC3193229.

Berger MF, Lawrence MS, Demichelis F, Drier Y, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko AY, Sboner A, Esgueva R, Pflueger D, Sougnez C, Onofrio R, Carter SL, Park K, Habegger L, Ambrogio L, Fennell T, Parkin M, Saksena G, Voet D, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Wilkinson J, Fisher S, Winckler W, Mahan S, Ardlie K, Baldwin J, Simons JW, Kitabayashi N, MacDonald TY, Kantoff PW, Chin L, Gabriel SB, Gerstein MB, Golub TR, Meyerson M, Tewari A, Lander ES, Getz G, Rubin MA, Garraway LA. The genomic complexity of primary human prostate cancer. Nature. 2011 Feb 10;470(7333):214-20. doi: 10.1038/nature09744. PMID: 21307934; PMCID: PMC3075885.

Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012 Oct 4;490(7418):61-70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. Epub 2012 Sep 23. PMID: 23000897; PMCID: PMC3465532.

Chang MT, Penson A, Desai NB, Socci ND, Shen R, Seshan VE, Kundra R, Abeshouse A, Viale A, Cha EK, Hao X, Reuter VE, Rudin CM, Bochner BH, Rosenberg JE, Bajorin DF, Schultz N, Berger MF, Iyer G, Solit DB, Al-Ahmadie HA, Taylor BS. Small-Cell Carcinomas of the Bladder and Lung Are Characterized by a Convergent but Distinct Pathogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Apr 15;24(8):1965-1973. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2655. Epub 2017 Nov 27. PMID: 29180607; PMCID: PMC5965261.

Qiu W, Hu M, Sridhar A, Opeskin K, Fox S, Shipitsin M, Trivett M, Thompson ER, Ramakrishna M, Gorringe KL, Polyak K, Haviv I, Campbell IG. No evidence of clonal somatic genetic alterations in cancer-associated fibroblasts from human breast and ovarian carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2008 May;40(5):650-5. doi: 10.1038/ng.117. Epub 2008 Apr 13. PMID: 18408720; PMCID: PMC3745022.

Rosen H, Krichevsky A, Polakiewicz RD, Benzakine S, Bar-Shavit Z. Developmental regulation of proenkephalin gene expression in osteoblasts. Mol Endocrinol. 1995 Nov;9(11):1621-31. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.11.8584038. PMID: 8584038.

Stasko SE, Wagner GF. Stanniocalcin gene expression during mouse urogenital development: a possible role in mesenchymal-epithelial signalling. Dev Dyn. 2001 Jan;220(1):49-59. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1086>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID: 11146507.

Khatun M, Modhukur V, Piltonen TT, Tapanainen JS, Salumets A. Stanniocalcin Protein Expression in Female Reproductive Organs: Literature Review and Public Cancer Database Analysis. Endocrinology. 2024 Aug 27;165(10):bqae110. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqae110. PMID: 39186548; PMCID: PMC11398916.

Liu AY. Cell-to-cell communication in prostate differentiation and cancer. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 2024; 5:1338-1348.

Liu AY. How to rejuvenate the prostate damaged by cancer. Regen Med Rep 2025, 2:61-66.

Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Physiology and function of the tight junction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009 Aug;1(2):a002584. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002584. PMID: 20066090; PMCID: PMC2742087.

Büyücek S, Viehweger F, Reiswich V, Gorbokon N, Chirico V, Bernreuther C, Lutz F, Kind S, Schlichter R, Weidemann S, Clauditz TS, Hinsch A, Bawahab AA, Jacobsen F, Luebke AM, Dum D, Hube-Magg C, Kluth M, Möller K, Menz A, Marx AH, Krech T, Lebok P, Fraune C, Sauter G, Simon R, Burandt E, Minner S, Steurer S, Lennartz M, Freytag M. Reduced occludin expression is related to unfavorable tumor phenotype and poor prognosis in many different tumor types: A tissue microarray study on 16,870 tumors. PLoS One. 2025 Apr 2;20(4):e0321105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321105. PMID: 40173205; PMCID: PMC11964279.

Hewitt KJ, Agarwal R, Morin PJ. The claudin gene family: expression in normal and neoplastic tissues. BMC Cancer. 2006 Jul 12;6:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-186. PMID: 16836752; PMCID: PMC1538620.

Orea MJ, Angulo JC, González-Corpas A, Echegaray D, Marvá M, Lobo MVT, Colás B, Ropero S. Claudin-3 Loss of Expression Is a Prognostic Marker in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 2;24(1):803. doi: 10.3390/ijms24010803. PMID: 36614243; PMCID: PMC9820886.

Vêncio EF, Pascal LE, Page LS, Denyer G, Wang AJ, Ruohola-Baker H, Zhang S, Wang K, Galas DJ, Liu AY. Embryonal carcinoma cell induction of miRNA and mRNA changes in co-cultured prostate stromal fibromuscular cells. J Cell Physiol. 2011 Jun;226(6):1479-88. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22464. PMID: 20945389; PMCID: PMC3968429.

van der Voort R, Taher TE, Derksen PW, Spaargaren M, van der Neut R, Pals ST. The hepatocyte growth factor/Met pathway in development, tumorigenesis, and B-cell differentiation. Adv Cancer Res. 2000;79:39-90. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(00)79002-6. PMID: 10818677.

Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. miR-21: a small multi-faceted RNA. J Cell Mol Med. 2009 Jan;13(1):39-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. PMID: 19175699; PMCID: PMC3823035.

Brockes JP, Gates PB. Mechanisms underlying vertebrate limb regeneration: lessons from the salamander. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014 Jun;42(3):625-30. doi: 10.1042/BST20140002. PMID: 24849229.

Vitello EA, Quek SI, Kincaid H, Fuchs T, Crichton DJ, Troisch P, Liu AY. Cancer-secreted AGR2 induces programmed cell death in normal cells. Oncotarget. 2016 Aug 2;7(31):49425-49434. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9921. PMID: 27283903; PMCID: PMC5226518.

Fessart D, Domblides C, Avril T, Eriksson LA, Begueret H, Pineau R, Malrieux C, Dugot-Senant N, Lucchesi C, Chevet E, Delom F. Secretion of protein disulphide isomerase AGR2 confers tumorigenic properties. Elife. 2016 May 30;5:e13887. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13887. PMID: 27240165; PMCID: PMC4940162.

Ho ME, Quek SI, True LD, Seiler R, Fleischmann A, Bagryanova L, Kim SR, Chia D, Goodglick L, Shimizu Y, Rosser CJ, Gao Y, Liu AY. Bladder cancer cells secrete while normal bladder cells express but do not secrete AGR2. Oncotarget. 2016 Mar 29;7(13):15747-56. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7400. PMID: 26894971; PMCID: PMC4941274.

Ho ME, Quek SI, True LD, Morrissey C, Corey E, Vessella RL, Dumpit R, Nelson PS, Maresh EL, Mah V, Alavi M, Kim SR, Bagryanova L, Horvath S, Chia D, Goodglick L, Liu AY. Prostate cancer cell phenotypes based on AGR2 and CD10 expression. Mod Pathol. 2013 Jun;26(6):849-59. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.238. Epub 2013 Jan 25. PMID: 23348903; PMCID: PMC3638070.

Dall'Era MA, True LD, Siegel AF, Porter MP, Sherertz TM, Liu AY. Differential expression of CD10 in prostate cancer and its clinical implication. BMC Urol. 2007 Mar 2;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-7-3. PMID: 17335564; PMCID: PMC1829163.

Fleischmann A, Rocha C, Saxer-Sekulic N, Zlobec I, Sauter G, Thalmann GN. High CD10 expression in lymph node metastases from surgically treated prostate cancer independently predicts early death. Virchows Arch. 2011 Jun;458(6):741-8. doi: 10.1007/s00428-011-1084-z. Epub 2011 May 3. PMID: 21538124.

Wayner EA, Quek SI, Ahmad R, Ho ME, Loprieno MA, Zhou Y, Ellis WJ, True LD, Liu AY. Development of an ELISA to detect the secreted prostate cancer biomarker AGR2 in voided urine. Prostate. 2012 Jun 15;72(9):1023-34. doi: 10.1002/pros.21508. Epub 2011 Nov 9. PMID: 22072305.

Ruppender NS, Morrissey C, Lange PH, Vessella RL. Dormancy in solid tumors: implications for prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013 Dec;32(3-4):501-9. doi: 10.1007/s10555-013-9422-z. PMID: 23612741; PMCID: PMC3796576.

Cackowski FC, Heath EI. Prostate cancer dormancy and recurrence. Cancer Lett. 2022 Jan 1;524:103-108. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.037. Epub 2021 Oct 5. PMID: 34624433; PMCID: PMC8694498.

Liu D, Rudland PS, Sibson DR, Platt-Higgins A, Barraclough R. Human homologue of cement gland protein, a novel metastasis inducer associated with breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005 May 1;65(9):3796-805. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3823. PMID: 15867376.

Negi H, Merugu SB, Mangukiya HB, Li Z, Zhou B, Sehar Q, Kamle S, Yunus FU, Mashausi DS, Wu Z, Li D. Anterior Gradient-2 monoclonal antibody inhibits lung cancer growth and metastasis by upregulating p53 pathway and without exerting any toxicological effects: A preclinical study. Cancer Lett. 2019 May 1;449:125-134. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.025. Epub 2019 Jan 25. PMID: 30685412.

Schraps N, Port JC, Menz A, Viehweger F, Büyücek S, Dum D, Schlichter R, Hinsch A, Fraune C, Bernreuther C, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C, Möller K, Reiswich V, Luebke AM, Lebok P, Weidemann S, Sauter G, Lennartz M, Jacobsen F, Clauditz TS, Marx AH, Simon R, Steurer S, Mercanoglu B, Melling N, Hackert T, Burandt E, Gorbokon N, Minner S, Krech T, Lutz F. Prevalence and Significance of AGR2 Expression in Human Cancer. Cancer Med. 2024 Nov;13(21):e70407. doi: 10.1002/cam4.70407. PMID: 39533806; PMCID: PMC11557986.

Liu AY, Kanan AD, Radon TP, Shah S, Weeks ME, Foster JM, Sosabowski JK, Dumartin L, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T. AGR2, a unique tumor-associated antigen, is a promising candidate for antibody targeting. Oncotarget. 2019 Jul 2;10(42):4276-4289. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26945. PMID: 31303962; PMCID: PMC6611513.

Fleischmann A, Schlomm T, Huland H, Köllermann J, Simon P, Mirlacher M, Salomon G, Chun FH, Steuber T, Simon R, Sauter G, Graefen M, Erbersdobler A. Distinct subcellular expression patterns of neutral endopeptidase (CD10) in prostate cancer predict diverging clinical courses in surgically treated patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Dec 1;14(23):7838-42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1432. PMID: 19047112.

Dall'Era MA, Oudes A, Martin DB, Liu AY. HSP27 and HSP70 interact with CD10 in C4-2 prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2007 May 15;67(7):714-21. doi: 10.1002/pros.20558. PMID: 17342744.

Maresh EL, Mah V, Alavi M, Horvath S, Bagryanova L, Liebeskind ES, Knutzen LA, Zhou Y, Chia D, Liu AY, Goodglick L. Differential expression of anterior gradient gene AGR2 in prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010 Dec 13;10:680. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-680. PMID: 21144054; PMCID: PMC3009682.

Aggarwal R, Huang J, Alumkal JJ, Zhang L, Feng FY, Thomas GV, Weinstein AS, Friedl V, Zhang C, Witte ON, Lloyd P, Gleave M, Evans CP, Youngren J, Beer TM, Rettig M, Wong CK, True L, Foye A, Playdle D, Ryan CJ, Lara P, Chi KN, Uzunangelov V, Sokolov A, Newton Y, Beltran H, Demichelis F, Rubin MA, Stuart JM, Small EJ. Clinical and Genomic Characterization of Treatment-Emergent Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A Multi-institutional Prospective Study. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Aug 20;36(24):2492-2503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6880. Epub 2018 Jul 9. PMID: 29985747; PMCID: PMC6366813.

Pece S, Tosoni D, Confalonieri S, Mazzarol G, Vecchi M, Ronzoni S, Bernard L, Viale G, Pelicci PG, Di Fiore PP. Biological and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers correlates with their cancer stem cell content. Cell. 2010 Jan 8;140(1):62-73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.007. PMID: 20074520.

Meyer MJ, Fleming JM, Lin AF, Hussnain SA, Ginsburg E, Vonderhaar BK. CD44posCD49fhiCD133/2hi defines xenograft-initiating cells in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010 Jun 1;70(11):4624-33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3619. Epub 2010 May 18. PMID: 20484027; PMCID: PMC4129519.

Liu AY. The Cancer Stem Cell Concept as Applied to Prostate Cancer. IgMin Res. January 22, 2026; 4(1): 020-031. IgMin ID: igmin329; DOI:10.61927/igmin329; Available at: igmin.link/p329

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

Department of Urology, Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA

Address Correspondence:

Alvin Y Liu, Department of Urology, Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Liu AY. The Cancer Stem Cell Concept as Applied to Prostate Cancer. IgMin Res. January 22, 2026; 4(1): 020-031. IgMin ID: igmin329; DOI:10.61927/igmin329; Available at: igmin.link/p329

Copyright: © 2026 Liu AY. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Prostate cancer cell types. In the PCA space, tran...

Figure 1: Prostate cancer cell types. In the PCA space, tran...

Figure 2: Stem cell factor expression in prostate cancer cel...

Figure 2: Stem cell factor expression in prostate cancer cel...

Figure 3: Reprogramming of adenocarcinoma LuCaP 70CR. The PC...

Figure 3: Reprogramming of adenocarcinoma LuCaP 70CR. The PC...

Figure 4: Prostate cancer cell dedifferentiation and differe...

Figure 4: Prostate cancer cell dedifferentiation and differe...

Table 1: Stem cell secreted proteins. Listed are genes enco...

Table 1: Stem cell secreted proteins. Listed are genes enco...

Tan BT, Park CY, Ailles LE, Weissman IL. The cancer stem cell hypothesis: a work in progress. Lab Invest. 2006 Dec;86(12):1203-7. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700488. Epub 2006 Oct 30. PMID: 17075578.

Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997 Jul;3(7):730-7. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. PMID: 9212098.

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Apr 1;100(7):3983-8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. Epub 2003 Mar 10. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 May 27;100(11):6890. PMID: 12629218; PMCID: PMC153034.

Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, Bonn VE, Hawkins C, Squire J, Dirks PB. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003 Sep 15;63(18):5821-8. PMID: 14522905.

Hemmati HD, Nakano I, Lazareff JA, Masterman-Smith M, Geschwind DH, Bronner-Fraser M, Kornblum HI. Cancerous stem cells can arise from pediatric brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Dec 9;100(25):15178-83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036535100. Epub 2003 Nov 26. PMID: 14645703; PMCID: PMC299944.

Nguyen HM, Vessella RL, Morrissey C, Brown LG, Coleman IM, Higano CS, Mostaghel EA, Zhang X, True LD, Lam HM, Roudier M, Lange PH, Nelson PS, Corey E. LuCaP Prostate Cancer Patient-Derived Xenografts Reflect the Molecular Heterogeneity of Advanced Disease an--d Serve as Models for Evaluating Cancer Therapeutics. Prostate. 2017 May;77(6):654-671. doi: 10.1002/pros.23313. Epub 2017 Feb 3. PMID: 28156002; PMCID: PMC5354949.

Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Vessella RL, Ware CB, Vêncio EF, Denyer G, Liu AY. Lineage relationship of prostate cancer cell types based on gene expression. BMC Med Genomics. 2011 May 23;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-46. PMID: 21605402; PMCID: PMC3113924.

Lee CJ, Dosch J, Simeone DM. Pancreatic cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jun 10;26(17):2806-12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6702. PMID: 18539958.

Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, Liu R, Wang X, Cho RW, Hoey T, Gurney A, Huang EH, Simeone DM, Shelton AA, Parmiani G, Castelli C, Clarke MF. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Jun 12;104(24):10158-63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. Epub 2007 Jun 4. PMID: 17548814; PMCID: PMC1891215.

Mallika L, Rajarathinam M, Thangavel S. Cancer stem cells in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its associated markers: A review. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2024 Apr 1;67(2):250-258. doi: 10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_467_23. Epub 2023 Nov 9. PMID: 38394427.

Patrawala L, Calhoun T, Schneider-Broussard R, Li H, Bhatia B, Tang S, Reilly JG, Chandra D, Zhou J, Claypool K, Coghlan L, Tang DG. Highly purified CD44+ prostate cancer cells from xenograft human tumors are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic progenitor cells. Oncogene. 2006 Mar 16;25(12):1696-708. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209327. PMID: 16449977.

Liu AY, True LD. Characterization of prostate cell types by CD cell surface molecules. Am J Pathol. 2002 Jan;160(1):37-43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64346-5. PMID: 11786396; PMCID: PMC1867111.

Liu AY, Roudier MP, True LD. Heterogeneity in primary and metastatic prostate cancer as defined by cell surface CD profile. Am J Pathol. 2004 Nov;165(5):1543-56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63412-8. PMID: 15509525; PMCID: PMC1618667.

Quek SI, Ho ME, Loprieno MA, Ellis WJ, Elliott N, Liu AY. A multiplex assay to measure RNA transcripts of prostate cancer in urine. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045656. Epub 2012 Sep 20. PMID: 23029164; PMCID: PMC3447789.

Liu AY. Differential expression of cell surface molecules in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2000 Jul 1;60(13):3429-34. PMID: 10910052.

Oudes AJ, Campbell DS, Sorensen CM, Walashek LS, True LD, Liu AY. Transcriptomes of human prostate cells. BMC Genomics. 2006 Apr 25;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-92. PMID: 16638148; PMCID: PMC1553448.

Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Goo YA, Page LS, Shadle CP, Liu AY. Temporal expression profiling of the effects of secreted factors from prostate stromal cells on embryonal carcinoma stem cells. Prostate. 2009 Sep 1;69(12):1353-65. doi: 10.1002/pros.20982. PMID: 19455603.

Vêncio RZ, Koide T. HTself: self-self based statistical test for low replication microarray studies. DNA Res. 2005;12(3):211-4. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi007. PMID: 16303752.

Liu AY, Vêncio RZ, Page LS, Ho ME, Loprieno MA, True LD. Bladder expression of CD cell surface antigens and cell-type-specific transcriptomes. Cell Tissue Res. 2012 Jun;348(3):589-600. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1383-y. Epub 2012 Mar 20. PMID: 22427119; PMCID: PMC3367057.

Pascal LE, Oudes AJ, Petersen TW, Goo YA, Walashek LS, True LD, Liu AY. Molecular and cellular characterization of ABCG2 in the prostate. BMC Urol. 2007 Apr 10;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-7-6. PMID: 17425799; PMCID: PMC1853103.

Hirschmann-Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG, Nuchtern JG, Jax TW, Gobel U, Goodell MA, Brenner MK. A distinct "side population" of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Sep 28;101(39):14228-33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400067101. Epub 2004 Sep 20. PMID: 15381773; PMCID: PMC521140.

Patel BJ, Pantuck AJ, Zisman A, Tsui KH, Paik SH, Caliliw R, Sheriff S, Wu L, deKernion JB, Tso CL, Belldegrun AS. CL1-GFP: an androgen independent metastatic tumor model for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2000 Oct;164(4):1420-5. PMID: 10992426.

Liu AY, Brubaker KD, Goo YA, Quinn JE, Kral S, Sorensen CM, Vessella RL, Belldegrun AS, Hood LE. Lineage relationship between LNCaP and LNCaP-derived prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2004 Jul 1;60(2):98-108. doi: 10.1002/pros.20031. PMID: 15162376.

Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007 Dec 21;318(5858):1917-20. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. Epub 2007 Nov 20. PMID: 18029452.

Vêncio EF, Nelson AM, Cavanaugh C, Ware CB, Milller DG, Garcia JC, Vêncio RZ, Loprieno MA, Liu AY. Reprogramming of prostate cancer-associated stromal cells to embryonic stem-like. Prostate. 2012 Sep 15;72(13):1453-63. doi: 10.1002/pros.22497. Epub 2012 Feb 7. PMID: 22314551.

Ring KL, Tong LM, Balestra ME, Javier R, Andrews-Zwilling Y, Li G, Walker D, Zhang WR, Kreitzer AC, Huang Y. Direct reprogramming of mouse and human fibroblasts into multipotent neural stem cells with a single factor. Cell Stem Cell. 2012 Jul 6;11(1):100-9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.018. Epub 2012 Jun 7. PMID: 22683203; PMCID: PMC3399516.

Borges GT, Vêncio EF, Quek SI, Chen A, Salvanha DM, Vêncio RZ, Nguyen HM, Vessella RL, Cavanaugh C, Ware CB, Troisch P, Liu AY. Conversion of Prostate Adenocarcinoma to Small Cell Carcinoma-Like by Reprogramming. J Cell Physiol. 2016 Sep;231(9):2040-7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25313. Epub 2016 Feb 4. PMID: 26773436.

Kanan AD, Corey E, Vêncio RZN, Ishwar A, Liu AY. Lineage relationship between prostate adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2019 May 30;19(1):518. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5680-7. PMID: 31146720; PMCID: PMC6543672.

Pascal LE, Vêncio RZ, Page LS, Liebeskind ES, Shadle CP, Troisch P, Marzolf B, True LD, Hood LE, Liu AY. Gene expression relationship between prostate cancer cells of Gleason 3, 4 and normal epithelial cells as revealed by cell type-specific transcriptomes. BMC Cancer. 2009 Dec 18;9:452. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-452. PMID: 20021671; PMCID: PMC2809079.

Williamson SR, Zhang S, Yao JL, Huang J, Lopez-Beltran A, Shen S, Osunkoya AO, MacLennan GT, Montironi R, Cheng L. ERG-TMPRSS2 rearrangement is shared by concurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma and prostatic small cell carcinoma and absent in small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: evidence supporting monoclonal origin. Mod Pathol. 2011 Aug;24(8):1120-7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.56. Epub 2011 Apr 15. PMID: 21499238; PMCID: PMC3441178.

Newcomb LF, Thompson IM Jr, Boyer HD, Brooks JD, Carroll PR, Cooperberg MR, Dash A, Ellis WJ, Fazli L, Feng Z, Gleave ME, Kunju P, Lance RS, McKenney JK, Meng MV, Nicolas MM, Sanda MG, Simko J, So A, Tretiakova MS, Troyer DA, True LD, Vakar-Lopez F, Virgin J, Wagner AA, Wei JT, Zheng Y, Nelson PS, Lin DW; Canary PASS Investigators. Outcomes of Active Surveillance for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer in the Prospective, Multi-Institutional Canary PASS Cohort. J Urol. 2016 Feb;195(2):313-20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.087. Epub 2015 Aug 29. PMID: 26327354; PMCID: PMC4970462.

Liu AY. Prostate cancer research: tools, cell types, and molecular targets. Front Oncol. 2024 Mar 26;14:1321694. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1321694. PMID: 38595814; PMCID: PMC11002103.

Epstein JI, Amin MB, Beltran H, Lotan TL, Mosquera JM, Reuter VE, Robinson BD, Troncoso P, Rubin MA. Proposed morphologic classification of prostate cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014 Jun;38(6):756-67. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000208. PMID: 24705311; PMCID: PMC4112087.

Liu AY. The opposing action of stromal cell proenkephalin and stem cell transcription factors in prostate cancer differentiation. BMC Cancer. 2021 Dec 15;21(1):1335. doi: 10.1186/s12885-021-09090-y. PMID: 34911496; PMCID: PMC8675470.

Albino D, Civenni G, Dallavalle C, Roos M, Jahns H, Curti L, Rossi S, Pinton S, D'Ambrosio G, Sessa F, Hall J, Catapano CV, Carbone GM. Activation of the Lin28/let-7 Axis by Loss of ESE3/EHF Promotes a Tumorigenic and Stem-like Phenotype in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016 Jun 15;76(12):3629-43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2665. Epub 2016 May 2. PMID: 27197175.

Jeter CR, Liu B, Lu Y, Chao HP, Zhang D, Liu X, Chen X, Li Q, Rycaj K, Calhoun-Davis T, Yan L, Hu Q, Wang J, Shen J, Liu S, Tang DG. NANOG reprograms prostate cancer cells to castration resistance via dynamically repressing and engaging the AR/FOXA1 signaling axis. Cell Discov. 2016 Nov 15;2:16041. doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2016.41. PMID: 27867534; PMCID: PMC5109294.

Kosaka T, Mikami S, Yoshimine S, Miyazaki Y, Daimon T, Kikuchi E, Miyajima A, Oya M. The prognostic significance of OCT4 expression in patients with prostate cancer. Hum Pathol. 2016 May;51:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.12.008. Epub 2015 Dec 30. PMID: 27067776.

Yu X, Cates JM, Morrissey C, You C, Grabowska MM, Zhang J, DeGraff DJ, Strand DW, Franco OE, Lin-Tsai O, Hayward SW, Matusik RJ. SOX2 expression in the developing, adult, as well as, diseased prostate. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014 Dec;17(4):301-9. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.29. Epub 2014 Aug 5. PMID: 25091041; PMCID: PMC4227931.

Cunha GR. Urogenital development: a four-part story of mesenchymal-epithelial interactions. Differentiation. 2010 Sep-Oct;80(2-3):79-80. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.08.004. Epub 2010 Sep 1. PMID: 20813448; PMCID: PMC4699566.