Purification of Monoacylglycerides using Urea

Plant Biology受け取った 17 Nov 2025 受け入れられた 23 Dec 2025 オンラインで公開された 26 Dec 2025

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Previous Full Text

How Increased CO2 Warms the Earth

受け取った 17 Nov 2025 受け入れられた 23 Dec 2025 オンラインで公開された 26 Dec 2025

Monoacylglycerides (MAGs) produced during conventional synthesis contain impurities such as diacylglycerides, triacylglycerides, and glycerol. In this study, urea was employed to form complexes with MAGs derived from palm oil (PO), canola oil (CO), fully hydrogenated palm oil (FHPO), and fully hydrogenated soybean oil (FHSO) in hot methanol. After crystallization and separation of the urea–MAG complexes, hydrochloric acid was used to release purified MAGs. The results demonstrated a significant increase in α-MAG content (from 39.8%, 40.4%, 42, 4 and 43.4% to 74%, 85.4%, 83.1%, and 51.9% for PO, FHPO, FHSO, and CO, respectively, p < 0.05). These results confirm the effectiveness of the urea complexation method for α-MAG purification.

Monoacylglycerides (MAGs) are widely used emulsifiers in food applications. Distilled MAGs containing ≥90% total MAG are available in soft plastic, flakes, beads, or powder forms. The soft form provides good aeration properties for low-moisture applications, whereas the hard form enhances baked product structure and shelf-life extension. Emulsifiers are typically applied at three concentration levels, depending on the α-MAG contribution to shortening, margarine, or specialty products [].

MAGs exist in two isomeric forms: α-MAG (1-MAG), where the fatty acid is attached at the terminal position of glycerol, and β-MAG (2-MAG), where the fatty acid is bonded at the central position. At room temperature, ~95% of MAGs are in the α-MAG form []. However, due to high distillation temperatures, commercially distilled products may contain only ~80% α-MAG, despite a total MAG content of ~95% []. Manufacturers typically report α-MAG content, which is ~10% lower than the total MAG content [].

MAGs are produced batchwise via a two-step process. In the first step, triacylglycerides react with excess glycerol in the presence of a catalyst at ~220 °C, yielding a mixture of MAGs and diacylglycerides. The product generally contains 35% - 50% MAG, with the remainder consisting of diacylglycerides, unreacted triacylglycerides (~10%), residual glycerol (3% - 4%), and free fatty acids (1% - 3%) [].

Purification methods such as molecular distillation and the Allsop–Kuhrat process have been reported [,]. These methods require specialized conditions, including low temperatures under vacuum. Urea, however, can form complexes with fatty acids, esters, and alcohols []. The yield of urea complexes depends on chain length, saturation, and isomeric configuration. Urea electively forms inclusion complexes with long-chain saturated fatty acids due to their linear structure and ability to fit into the hexagonal urea channels. In contrast, short-chain fatty acids and unsaturated fatty acids do not stabilize the urea lattice. The presence of double bonds introduces structural kinks that prevent complexation, and the degree and position of unsaturation further reduce the ability of the fatty acid to enter the urea channels. As a result, urea complexation effectively separates saturated from unsaturated fatty acids.

The objective of this study was to investigate the purification of MAGs via urea complexation.

Hydrochloric acid (37%), glycerol, chloroform, sodium hydroxide, methanol (all analytical grade), and sodium sulfate (anhydrous) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Filter paper (Whatman No. 91) was obtained from Whatman International Ltd. (Maidstone, England). Urea was supplied by Shiraz Petrochemical Company (Shiraz, Iran). Refined, bleached, and deodorized palm oil (PO; IV = 53.5) was obtained from Wilmar (Penang, Malaysia). Fully hydrogenated palm oil (FHPO; IV = 5.2), fully hydrogenated soybean oil (FHSO; IV = 4), and canola oil (CO; IV = 108) were supplied by Behshahr Industrial Company (Tehran, Iran). Iodine values were determined according to AOCS Official Method Cd 1d-92 [].

Glycerol (63 g) and oil (90 g) were heated to 220 °C in the presence of sodium hydroxide (0.18 g) under nitrogen for ~2 h. Fatty acid composition of the MAG mixture was determined using AOCS Official Method Ce 1e-91.

Prepared MAG (5 g, purity 35% - 50%) was dissolved in 120 mL of hot methanol containing 50 g urea. The mixture was refluxed for 5 min, cooled to 64 °C, and incubated at 60 °C for 5 min. The precipitate was filtered (Whatman No. 91) at 60 °C. The filtrate was stored at ~25 °C to complete crystallization. Crystals were dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water, heated to 60 °C, and treated with 1–2 mL of HCl (1N) to release MAGs. MAGs were extracted into chloroform (≥3 times), dried with sodium sulfate, and evaporated. Purity was measured according to AOCS Official Method Cd 11-57.

Methanol was recovered via distillation and reused. Urea was recrystallized after neutralization with sodium hydroxide and reused.

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance between impure and purified MAGs was determined using ANOVA. A p - value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

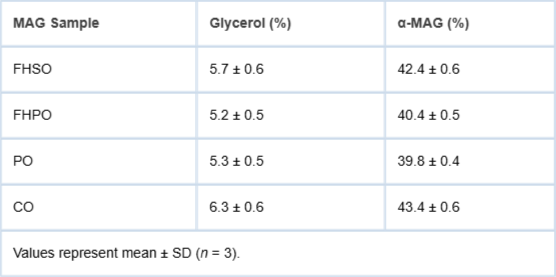

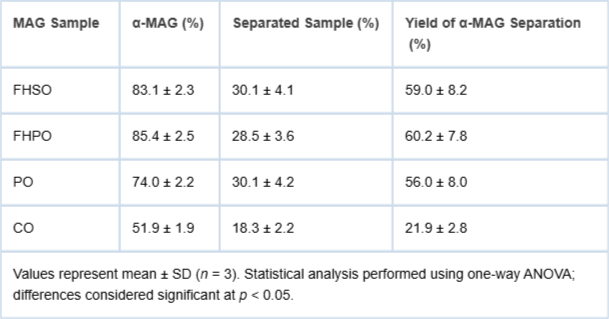

The α-MAG and glycerin contents of the impure monoacylglyceride (MAG) samples are presented in Table 2. After purification using the urea complexation method, key properties of the purified MAGs—including α-isomer content, separation yield, and α-MAG recovery—were evaluated and are shown in Table 3.

The α-MAG content in the impure MAGs ranged from 39.8% to 43.4%. Following purification, α-MAG levels increased significantly, ranging from 51.9% to 85.4%, demonstrating the effectiveness of urea complexation in enriching α-MAG.

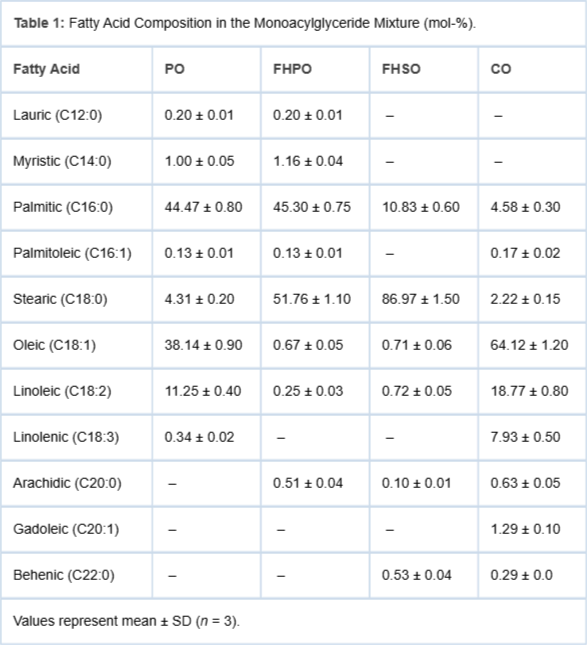

Fatty acid composition analysis (Table 1) revealed that fully hydrogenated palm oil (FHPO) and fully hydrogenated soybean oil (FHSO) contained high levels of saturated fatty acids (98.93% and 98.43%, respectively), whereas palm oil (PO) and canola oil (CO) had lower saturation levels (49.98% and 7.72%). The separation efficiency of α-MAG via urea complexation was notably higher in MAGs derived from saturated fats. This is attributed to stronger urea complex formation with saturated fatty acids such as stearic and palmitic acids. Accordingly, α-MAG levels in FHPO and FHSO increased from 40.4% and 42.4% to 85.4% and 83.1%, respectively—substantially higher than the increases observed for PO and CO. The slightly higher separation efficiency in FHPO compared to FHSO suggests that urea forms stronger complexes with palmitic acid than with stearic acid. For PO, α-MAG content increased from 39.8% to 74.0%, whereas CO showed a smaller improvement (43.4% to 51.9%), reflecting the lower stability of urea complexes with mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The separation yields presented in Table 3 further support this trend. MAGs derived from saturated fats not only exhibited higher α-MAG enrichment but also higher overall separation yields. FHPO and FHSO achieved yields of 60.2% and 59.0%, respectively, compared with 56.0% for PO and only 21.9% for CO. The low yield observed for CO corresponds to its very low saturation level.

The α-MAG concentrations achieved using this method (51.9%–85.4%) align with industrial MAG grades, which are typically produced at three levels: 40% to 60% α-MAG; 52% minimum α-MAG; and distilled or 90%, total MAG

While the method is suitable for producing grades 1 and 2, it is not ideal for achieving distilled MAG purity. However, its main advantage lies in its simplicity and sustainability. Unlike molecular distillation, which requires extreme conditions (e.g., 0.001 mmHg at 150 °C) [], this method operates under mild conditions and allows for the recycling of solvents and urea after appropriate purification steps.

This study demonstrated that urea complexation is an effective method for enriching α-monoacylglycerides (α-MAGs) from mixtures derived from palm oil, canola oil, fully hydrogenated palm oil, and fully hydrogenated soybean oil. The process significantly increased α-MAG content from ~40% in impure samples to 52%–85% in purified fractions (p < 0.05). The method was most effective for saturated oils (FHPO and FHSO), yielding α-MAG levels above 80% with reproducible results across replicates. Although the purity achieved did not reach the level of distilled MAGs (~90%), urea complexation offers a simple, sustainable, and statistically validated alternative to molecular distillation for industrial applications. In addition to its efficiency in purifying monoacylglycerides, the process demonstrates strong sustainability potential, as both urea and methanol can be recovered and reused, reducing chemical consumption and minimizing waste.

O’Brien RD. Fats and oils: formulating and processing for applications. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. 2003;268–270.

Bennion EB, Bamford GST. The technology of cakemaking. London (UK): Blackie Academic & Professional. 1997; 114–115.

Jungermann E, Sonntag NOV. Glycerine: a key cosmetic ingredient. New York (NY): Marcel Dekker. 1990;313–314.

Stauffer CE. Functional additives for bakery foods. Gaithersburg (MD): Aspen Publishers. 1990;88–89.

Hui YH. Bailey’s industrial oil & fat products. Vol. 4, Edible oil & fat products: processing technology. New York (NY): Wiley. 1996;572–592.

Alsop WG. Process for the preparation of higher fatty acid monoglycerides. US patent 3083216. 1963.

Kuhrt NE, Welch EA, Kovarik FJ. Molecularly distilled monoglyceride I. Preparation and properties. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1950;27:310–317.

Lkan R. Natural products: a laboratory guide. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier. 1991;39–41.

American Oil Chemists’ Society. Official methods and recommended practices of the AOCS. 5th ed. Champaign (IL): AOCS. 1998.

Shoaei E, Kalantari F, Golalizadeh S, Hamidi N. Purification of Monoacylglycerides using Urea. IgMin Res. December 26, 2025; 3(12): 462-464. IgMin ID: igmin325; DOI:10.61927/igmin325; Available at: igmin.link/p325

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

R&D Laboratory, Behshahr Industrial Company, 8th Km, Fath Highway, Tehran, Iran

Address Correspondence:

Ehsan Shoaei, R&D Laboratory, Behshahr Industrial Company, 8th Km, Fath Highway, Tehran, Iran, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Shoaei E, Kalantari F, Golalizadeh S, Hamidi N. Purification of Monoacylglycerides using Urea. IgMin Res. December 26, 2025; 3(12): 462-464. IgMin ID: igmin325; DOI:10.61927/igmin325; Available at: igmin.link/p325

Copyright: 2025 Shoaei E, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Table 1: Fatty Acid Composition in the Monoacylglyceride Mi...

Table 1: Fatty Acid Composition in the Monoacylglyceride Mi...

Table 2: Characteristics of Impure Monoacylglycerides....

Table 2: Characteristics of Impure Monoacylglycerides....

Table 3: Characteristics of Separated and Purified Monoacyl...

Table 3: Characteristics of Separated and Purified Monoacyl...

O’Brien RD. Fats and oils: formulating and processing for applications. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. 2003;268–270.

Bennion EB, Bamford GST. The technology of cakemaking. London (UK): Blackie Academic & Professional. 1997; 114–115.

Jungermann E, Sonntag NOV. Glycerine: a key cosmetic ingredient. New York (NY): Marcel Dekker. 1990;313–314.

Stauffer CE. Functional additives for bakery foods. Gaithersburg (MD): Aspen Publishers. 1990;88–89.

Hui YH. Bailey’s industrial oil & fat products. Vol. 4, Edible oil & fat products: processing technology. New York (NY): Wiley. 1996;572–592.

Alsop WG. Process for the preparation of higher fatty acid monoglycerides. US patent 3083216. 1963.

Kuhrt NE, Welch EA, Kovarik FJ. Molecularly distilled monoglyceride I. Preparation and properties. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1950;27:310–317.

Lkan R. Natural products: a laboratory guide. Amsterdam (Netherlands): Elsevier. 1991;39–41.

American Oil Chemists’ Society. Official methods and recommended practices of the AOCS. 5th ed. Champaign (IL): AOCS. 1998.