Landing Site Selection for the First Human Mission to Mars

Aerospace Engineering受け取った 27 Jan 2026 受け入れられた 06 Feb 2026 オンラインで公開された 09 Feb 2026

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

END

Submit Article

受け取った 27 Jan 2026 受け入れられた 06 Feb 2026 オンラインで公開された 09 Feb 2026

NASA teams have clarified requirements for a landing site for the first human mission to Mars regarding important factors such as elevation, slope, winds, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, etc. Current planning in the NASA for a landing site for human missions to Mars community is aimed at mission architectures that utilize accessible H2O on Mars to produce several hundred tons of propellants for the return trip using the Starship. This limits the acceptable range of latitude to about 40°N, where observations from orbit suggest that accessible H2O might occur. In this paper, it is shown that a simpler, less demanding architecture for the first human landing on Mars could be carried out without requiring accessible H2O on Mars. With this mission model, the landing site could be chosen at an equatorial site, with several benefits in energy, thermal stability, and solar psychological environment, while avoiding the challenges of locating, verifying H2O, and validating and implementing processes for utilization. Proof of the existence of such accessible H2O requires ground truth, not yet attempted. It is suggested that NASA teams should also consider equatorial landing sites for mission architectures that do not require indigenous Mars H2O, which might be preferred for the first landing.

Layman’s explanation

With the advent of newly evolving very large, affordable launch vehicles, plans for the first human expedition to Mars have become focused on very ambitious mission concepts that require large amounts of indigenous Mars ice to produce propellants for the return flight from Mars – a significant challenge, complication, and cost and risk additive. This limits potential landing sites to non-equatorial latitudes, which introduces several disadvantages. I propose a smaller, less ambitious mission plan for the first human landing on Mars that doesn’t require Mars ice and therefore could land near the equator. I analyze the water supply for such a mission.

Mars is the planet most like Earth and might have resembled Earth even more in its early history, when liquid water might have been present. A human mission to Mars has been widely regarded as the ultimate goal for space exploration in our time. Robert Zubrin provided the arguments for such a mission [].

Platoff [] wrote a history covering 1952 to 1970. Portree [] wrote a history of mission planning for sending humans to Mars by the year 2000. Rapp [] extended that history to 2023.

According to Portree, More than 1,000 piloted Mars mission studies were conducted inside and outside NASA between about 1950 and 2000. Many were the product of NASA and industry study teams, while others were the work of committed individuals or private organizations.

NASA investigated options for a human mission to Mars in a series of so-called “Design Reference Missions”, later modified to “Design Reference Architectures,” that culminated in the extensive study: “DRA-5” [].

Despite all this ingenious planning for a human mission to Mars, NASA never seriously contemplated implementing a human mission to Mars because of the overall mission cost, including launch vehicle costs, the technical challenges, the difficulty in landing large payloads on Mars, the production of propellants for the return trip by processing Martian materials, and the recycling of waste products [].

Jones (2024) pointed out that historically, launch cost was a major impediment to exploring and exploiting space [,]. High launch costs led to high investment in space hardware development, which led to high space mission costs. The advent of the Starship by SpaceX with a putative affordable payload of up to 100 MT changes the rules for space exploration. SpaceX is thinking in far more extensive and grander terms than NASA [,]. However, while SpaceX claims that they will implement human missions on the Mars surface in the next few years, independent analysis argues that these claims are overly optimistic [,]. A great deal of preparatory work is required before SpaceX can safely land a human crew and return them from Mars. Nevertheless, if the Starship can deliver a 100 MT payload to the Mars surface affordably (while the largest payload yet landed was about 1 MT), that requires a totally new frame of reference for planning future Mars missions.

The advent of the SpaceX Starship with its much lower cost per MT and putative 100 MT payload provides new capabilities not imagined in previous Mars mission studies. The Starship changes the rules and requires revamping planning for human missions to Mars. Instead of minimizing mass, the appropriate approach now is to use mass to simplify and expedite the mission, reduce risk, and broaden the accomplishments of the mission.

In a series of postings and press releases on the Internet, SpaceX provided a rough outline of a very ambitious human mission to Mars based on the Starship, which was viewed as a first step toward the establishment of a settlement or colony on Mars [,]. A vital part of this mission (and indeed most Mars mission concepts) is the need for accessing large masses of indigenous Mars ice to use in the production of propellants for ascent from Mars as the first step in returning from Mars []. However, with the Starship, it is possible to implement a limited human mission to Mars without the need for indigenous Mars water – a great reduction in complexity, cost, and risk [].

A very important part of planning for a human mission to Mars is the selection of a landing site. The choice of landing site depends on several critical requirements, but if the mission calls for the utilization of indigenous Mars water, the availability of water becomes the predominant and overriding constraint on the choice of landing site. This includes most conceptual human missions to Mars. For a limited human mission to Mars that does not require indigenous Mars H2O, this requirement does not apply, thus opening up more options for landing sites, particularly making equatorial latitudes feasible.

The prevailing view in the NASA community seems to regard the need for indigenous Mars water in a human mission to Mars as crucial because they are focused on hypothetical large-scale settlements, so studies of potential landing sites have been dominated by locations that might provide accessible H2O. That is unfortunate because it drives up the cost, complexity, and risk of the first such mission, and equatorial sites are eliminated.

Informal groups of scientists and engineers arose in the NASA community about ten years ago to study and evaluate potential landing sites for a putative human mission to Mars that requires access to large amounts of indigenous ice on Mars. Several workshops were held on landing site selection, beginning with the important 2015 workshop, where several hundred attended, and about 40 papers were presented. This workshop concluded that the availability of indigenous Martian H2O was the major driving factor in site selection for a human mission to Mars []. However, the problem with such activities is that the first human mission to Mars has not yet been defined, and since landing site selection depends on the specifics of the human mission to Mars, attempting to select a landing site is like the proverbial “putting the cart before the horse”. Missions that require accessible H2O cannot go forward without an indigenous water supply, and this has been an important factor in previous site selection studies. However, as Rapp [] has shown, one can define a simpler, less costly, and less risky human mission to Mars without utilizing accessible water on Mars, and this simplified mission is ideally suited for the first landings on Mars. Since it doesn’t rely on accessible water on Mars, the landing site can be chosen at an equatorial latitude. Furthermore, as of this date, most of the postulated H2O deposits are still hypothetical, based on geological formations observed from orbit, and are not verified by ground truth []. On the other hand, it seems certain that later Mars missions at greater scale, after the first human landings, will require indigenous Mars H2O to produce propellants for the return trip, as well as to provide water for life support. For such advanced missions, the current series of studies of Mars landing sites would be appropriate. Nevertheless, because NASA has not yet explored widely for accessible water on Mars, we have only a fragmentary glimpse of the distribution of accessible H2O on Mars, and studies of landing sites today are likely to end up choosing sites at higher latitude than might someday be necessary if NASA ever carries out serious exploration for near-surface H2O [].

There are several generic requirements for a landing site that are independent of the specifics of the mission, related to elevation, slope, winds, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, etc. Recent analysis of requirements in these factors is valuable, but the focus on higher latitudes makes the specific locations vulnerable to new findings of accessible H2O at lower latitudes, and becomes irrelevant for mission architectures that don’t require Mars H2O.

A crucial aspect of any human mission to Mars is the architecture for return from Mars. One approach (presently advocated by SpaceX) provides an ascent vehicle that departs from the surface of Mars and delivers the returning crew and some cargo all the way to LEO (direct return from Mars). In this case, the ascent vehicle is the Earth Return Vehicle (ERV). The ERV must provide life support for the crew for the entire return trip. A large mass of propellants is required for the massive Starship to escape from the Mars surface. If a Starship is used as the ERV, it was estimated that over 600 MT of CH4 + O2 propellants would be needed []. This could only be produced from accessible H2O on Mars, and this architecture would place a rigid requirement for a landing site to have accessible H2O that could provide large amounts of CH4 + O2 propellants by reacting with atmospheric CO2. With the present very sketchy state of knowledge of the distribution of accessible H2O on Mars, landing sites are being contemplated at latitudes around 40°N under the belief that accessible H2O is likely to be there, but unlikely to occur at lower latitudes [,,].

An alternative architecture would be to utilize a small capsule to deliver the returning crew plus a small amount of cargo to rendezvous with an ERV waiting in Mars orbit, transferring crew and cargo to the ERV for the return flight to LEO. It was estimated that the propellant requirement to lift the capsule to the ERV is likely to be about 40 MT of CH4 + O2 propellants []. Rapp [] showed that these propellants could be generated by bringing 19.8 MT of H2O from Earth to react with about 24.2 MT of atmospheric CO2 []. Thus, the need for accessible water on Mars would be avoided. Therefore, the landing site could be chosen at an equatorial latitude if other requirements are met. Since such a simplified mission architecture is likely to be more affordable and practical in the short run than bringing a massive Starship home from the Mars surface, the current series of studies of landing sites would not apply to the first human landings on Mars insofar as latitude is concerned. The other contributions of these studies are valuable and relevant to early landings regarding elevation, slope, winds, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, etc.

Review of published material by NASA teams and analysis by this author.

Before considering possible landing sites for a human mission to Mars, it is important to review and consider two elements of a human mission to Mars that require large amounts of mass on the surface of Mars: propellants for ascent from Mars for the return trip, and water for life support while the crew is on the surface. For purposes of discussion, we assume a crew of six for a stay of 500 sols on Mars (see Appendix 1 for discussion of crew size and mission duration). The water requirements and options for providing the required water are discussed in the next sections.

Rapp (2024) reviewed the literature on requirements for water for life support in deep space missions [,]. Surprisingly, there do not seem to be any authoritative studies of the requirements for water in deep space missions and how different levels of water supply to the crew affect their ability to perform work, their emotional content, or even what is necessary for survival. There are, here and there, a few brief statements of requirements, but without a backup of any kind. The recent experience with the ISS might not be relevant because it provided low amounts of water for short-term stays at the ISS. Furthermore, recycling on the ISS depended on repeated “orbital replacement units” to account for subsystem failures.

The water requirement is expressed as the daily mass of water per crewmember per day (kg/CM/sol). Jones [] distinguished between his roughly estimated survival level of about 7 kg/CM/sol vs. an “Earth-like” water availability of about 27 kg/CM/sol. Rapp discussed pros and cons at length, and settled on an intermediate choice of 16.7 kg/CM/sol – that we use here [,].

The total requirement for a crew of six for 500 sols is thus estimated to be 6 × 500 × 16.7 kg, which would put the total water requirement for 500 sols at 50 MT. More than half of this requirement would be for laundry and showers. It would make sense to separate potable water from laundry/shower water. Recycling non-potable water ought to be relatively easy. If a long-life, reliable, 90% efficient liquid recycling system could be developed for non-potable water, the ~25 MT requirement for laundry/shower water would be reduced to 2.5 MT plus the mass of the recycling system (wild guess: 2.5 MT?). The mass requirement to be brought from Earth would then be 25 MT for potable water plus 5 MT for laundry/shower water, for a total of 30 MT.

Bringing 30 MT of water from Earth might be preferable to depending on a complex recycling system (for all wastewater) of uncertain reliability. For our purposes, we assume that bringing 30 MT from Earth would be the method of choice for early human landings on Mars. At worst, the 30 MT would provide more than 7 kg/CM/sol, postulated by Jones to be the survival level. The 30 MT would fit within the putative 100 MT payload of a Starship.

In a larger-scale human mission to Mars, where large amounts of Martian water would be utilized to produce propellants, water would be obtained from a Martian source, but it would require purification.

There is a significant difference between mission concepts for return from Mars between the SpaceX mission that would return the crew and Mars samples in a 100+ MT Starship, directly from the surface of Mars to LEO [,] vs. the smaller, less demanding approach described by Rapp using a 9 MT capsule to go from the Mars surface to Mars orbit []. The SpaceX mission concept has the simplicity of involving a single vehicle that leaves LEO, lands on Mars, and then departs from Mars to return directly to LEO, avoiding rendezvous in Mars orbit. But with a crew of twelve, this entails several challenges, including the need for a large number of heavy-lift launches to fuel several Starships in LEO, and the need to obtain large masses of Mars H2O for propellant production. The smaller, less demanding mission avoids the need to obtain water from Mars – a great simplification –, but it adds the complexity of a Mars rendezvous crew transfer. These two alternatives are discussed in the next sections.

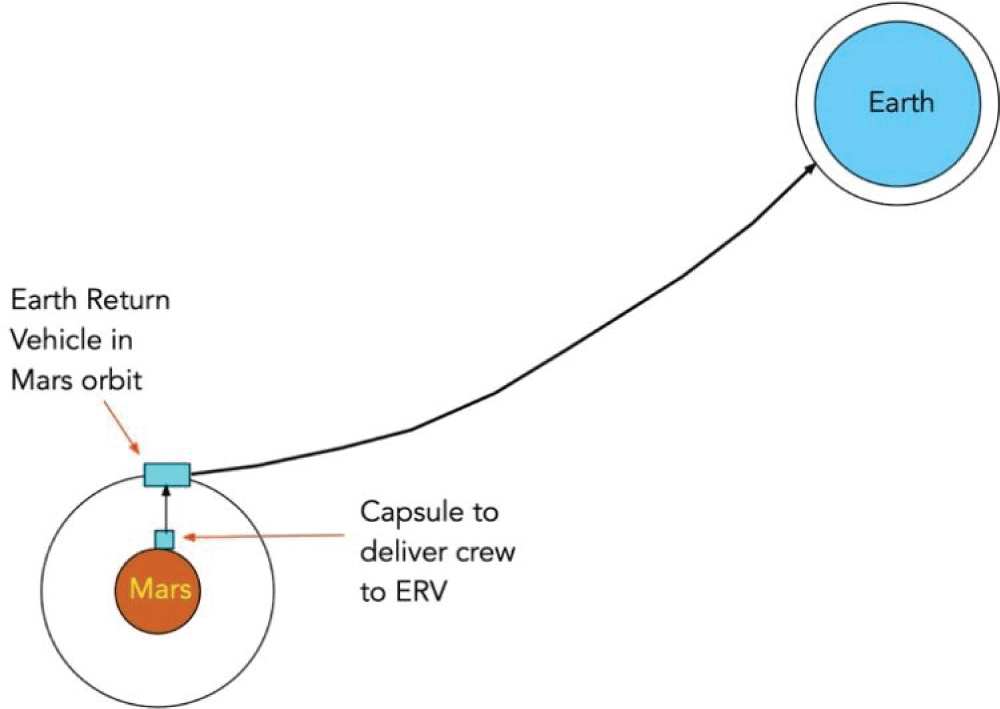

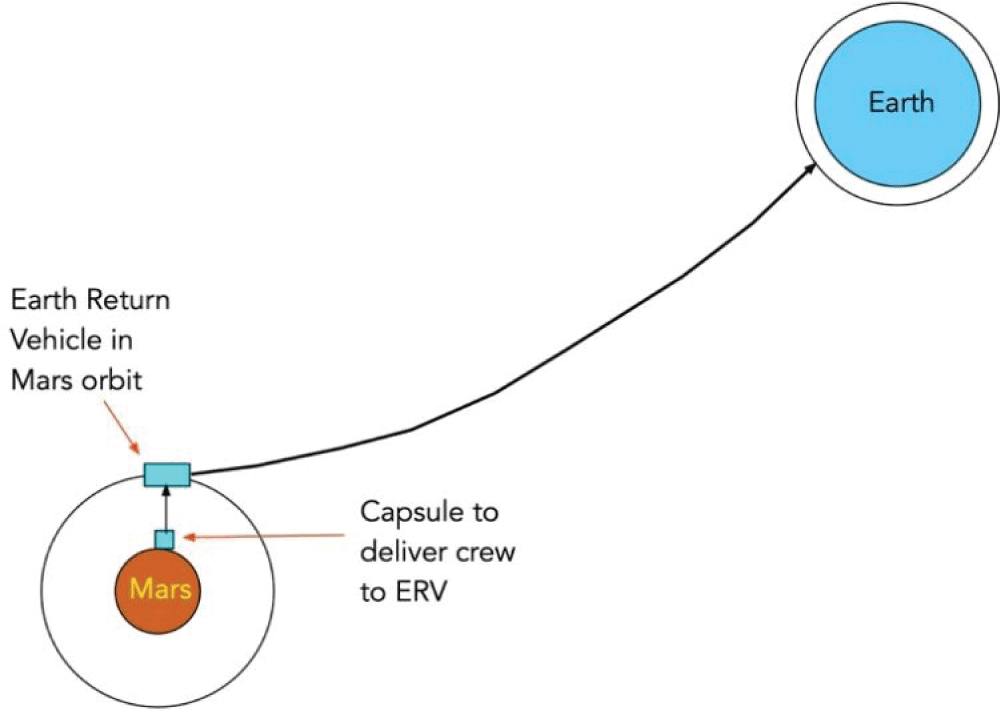

In some ways, the lesser mission is patterned after NASA’s “DRA-5”, an extended study of a human mission to Mars of about two decades ago, before new developments in large, affordable launch vehicles. Rapp provided a brief description of a modernized mission, based loosely on DRA-5, that he called “DRA-6” []. A Starship delivers a crew of 6 to the Mars surface. The surface stay is of the rough order of 500 sols. In return, a small ascent capsule lifts off to rendezvous and transfer the crew to a separate Earth Return Vehicle (ERV) in Mars orbit. In this mission, two additional vehicles are needed in addition to the Starship, and a rendezvous crew transfer maneuver is introduced. The DRA-6 mission requires only 40 MT of ascent propellants for a crew of 6 [] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Plan for return from Mars using a capsule to deliver the crew to a waiting ERV in Mars orbit.

Figure 1: Plan for return from Mars using a capsule to deliver the crew to a waiting ERV in Mars orbit.This was the plan for a human mission to Mars in a mass-limited era when the DRA-5 study was carried out []. In DRA-5, the required 40 MT of ascent propellants were expected to be produced from indigenous Mars H2O and CO2 resources to minimize mass brought from Earth. Rapp proposed to use the same approach for return from Mars, but instead of relying on indigenous H2O from Mars, he utilized the high payload capacity of the Starship to bring 19.8 MT of water from Earth to produce propellants without use of water from Mars, thus avoiding the risky, time-consuming, expensive search for accessible H2O on Mars, and allowing landing at potential sites at equatorial latitude, independent of any possible endowment with near-surface H2O [].

We assume here a mixture ratio (by mass) of 22% CH4 and 78% O2. [] The ascent propellant requirement for DRA-6 is therefore about 8.8 MT of CH4 and 31.2 MT of O2 (total of ~ 40 MT). The propellants contain 6.6 MT of carbon, 2.2 MT of hydrogen, and 31.2 MT of oxygen.

In DRA-6, the 2.2 MT of hydrogen is supplied by bringing 19.8 MT of water from Earth. The 6.6 MT of carbon is supplied by 24.2 MT of Martian CO2. (See Appendix 1 of []) The total oxygen production is 35.2 MT. of which 31.2 MT is used as propellant, and 4.0 MT is extra O2.

SpaceX briefly described a planned human mission to Mars in several Internet postings [,]. Return from Mars utilizes a ~ 100 MT Starship, and the payload it carries for the return flight was not specified, but we hazard a guess of 10 MT, so the dry mass of the Starship (independent of propellants) is estimated to be about 110 MT. Each Starship delivers six crewmembers to Mars, and the plan called for two Starships to deliver a full crew of twelve. It is not clear whether the return will involve two Starships, each carrying 6 crewmembers, or one Starship carrying 12 crewmembers.

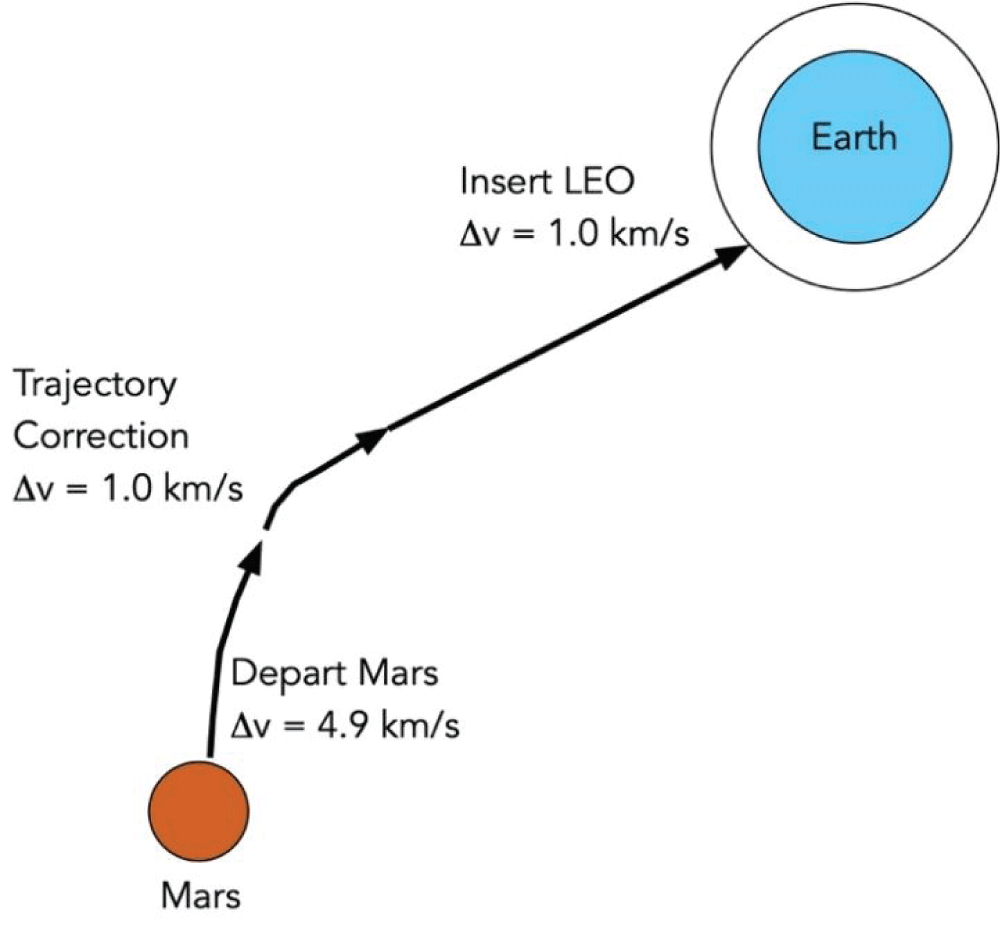

We can divide direct return from Mars into three steps: depart the Mars gravity field, mid-course correction, and assist in inserting into LEO (Figure 2). Starting with a 110 MT loaded Starship and 628 MT of CH4 +O2 propellants (total mass = 738 MT), Rapp estimated that the rockets on the Starship burn 547 MT of propellants to overcome a ∆v = 4.9 km/s, leaving the 110 MT Starship holding 81 MT of propellant outside the influence of Mars gravity [,]. The Starship then burns 46.1 MT of propellants for a ∆v = 1.0 km/s for a course correction to point toward Earth. Arriving at Earth, the Starship burns a final 34.9 MT of propellants for a ∆v = 1.0 km/s to assist in LEO insertion []. In this simple calculation, no allowance was made for residual propellant in LEO. The total propellant requirement on Mars was estimated by Rapp to be 628 MT, of which about 138.2 MT is CH4 and about 489.8 MT is O2.

Rapp described production of propellants requiring a multistep process: electrolysis of H2O, Sabatier reaction of H2 with CO2, electrolysis of H2O, and a second Sabatier step [,]. To produce 138.2 MT CH4 and 489.8 MT O2 propellants, 310.9 MT of Mars H2O is required to react with 380.0 MT of Martian CO2. This supplies the required 34.5 MT of hydrogen and 103.6 MT of carbon. The products are 138.2 MT CH4 and 552.6 MT O2. Excess O2 is produced, and 489.8 MT of O2 is used for propellants, and an extra 62.8 MT of O2 might be used for life support.

Most of the discussions of a human mission to Mars focused on getting there and back. The question of what to do on the surface of Mars does not seem to have been addressed to any depth. In addition, the vision of how many landings and at which sites requires further examination. If the original landing(s) take place at an equatorial site where there is no water, and accessible Mars water is enabling for later, more ambitious missions, how are these choices of landing site related? Lacking any long-range plan for exploration of Mars, there is a void of information on such questions. Furthermore, experience shows that long-range plans are usually overly optimistic and are typically discarded soon after they are produced. (This writer speaks from extensive experience in the NASA community.

For our purposes here, we make the following assumptions regarding the first human missions to Mars.

The landing site will be at an equatorial latitude, at a site of some significant scientific interest.

A very well-equipped laboratory will be installed that can carry out many of the analyses that would have been planned for a Mars Sample Return mission.

A network of Mars rovers will be placed at strategic locations on Mars to study local areas and acquire samples.

Commands to rovers from the main landing site will be transmitted via two communications satellites in Mars orbit, reducing the delay time (from Earth) of up to 40 minutes to just a few seconds, thus greatly improving rover capability.

Some means will be found to transport samples from remote locations to the main landing site.

The main occupation of the crew at the main landing site will be to manage the operation of remote rovers and analyze samples returned to the main site. See Appendix 3 for further discussion.

The mission concept is built around the supposition that a means can be found to transport samples from a wide swath of the Mars surface to an advanced laboratory at the main landing site. At this time, no such technology exists. It would have to be developed, despite great challenges due to the thin atmosphere and the rocky terrain. If development of such technology lagged behind readiness for a human mission to Mars, the mission would still have value because of the huge reduction in delay time in commanding rovers. A rover controlled on Mars can accomplish far more than a rover controlled from Earth, with its great time delay.

Any discussion for the choice of landing site for a human mission on Mars must begin with a selection of criteria for judging the worth of any proposed landing site. The criteria depend on the mission. (For example, if indigenous Mars water is required, the rarity of accessible water assures that accessible water becomes the crucial determining factor in site selection).

Although the criteria for a robotic mission to Mars must differ from those for a human mission to Mars, fundamentally because the robotic mission does not require a return, there is quite a bit of overlap in the requirements for both. Based on workshops and extensive studies, Golombek, et al. [] conducted a very in-depth search for an optimum landing site of the Mars Exploration Rover – an unmanned mission. They developed the following criteria:

(1) Latitude (10°N–15°S) for maximum solar power. (Note that for a human mission powered by nuclear reactors, the need for solar power is likely to be far less important, although it might still be useful for vehicles, remote installations and facilities, and backup for temporary outages.)

(2) Elevation sufficiently deep for high atmospheric density to enhance entry, descent, and landing (EDL). (Twenty years later, Golombek, et al. [] examined sites for a human mission to Mars where the elevation with respect to the MOLA geoid was typically about –3.9 km.)

(3) Low horizontal winds, shear, and turbulence in the last few kilometers to minimize horizontal velocity. The study did not discuss how winds vary with location, but mentioned the use of small horizontal rockets to compensate during descent. The 2022 study did not seem to cover winds.

(4) Upper limit to slopes. The criterion in 2003 was less than 9 m change in height per 100 m of horizontal distance (9% grade). This was later changed to a maximum of 5% slope in the 2022 study. Even this seems high to this writer.

(5) Upper limit to rock abundance. The limit in 2003 was regarding the safety of airbags used in landings. An upper limit of 20% rock coverage was set on the landing sites, which corresponds to roughly 1% area covered by 0.5 m high rocks based on modeled rock size-frequency distributions. The 2022 study required that the chance of impacting a rock greater than 0.5 m high (1 m diameter) should be <5%. Rock abundance was modeled by Golombek and coworkers [,].

(6) Radar-reflective, load-bearing, and trafficable surface safe for landing that is not dominated by fine-grained dust. The radar altimeter requires a radar reflective surface to properly measure the closing velocity. Dust could also coat rocks, obscuring their composition and/or mineralogy to remote sensing instruments, and dust could be deposited on the solar panels, reducing the surface mission lifetime. The descent imaging and processing system requires an adequate surface contrast to locate and match features for the measurement of horizontal velocity, and very dusty areas have uniform albedo, which could impede the effectiveness of this system.

Golombek, et al. [] updated requirements for a human mission to Mars. They discussed engineering constraints: related to elevation, latitude, surface slopes, rocks, and the presence of a load-bearing surface. An elevation is required below -2 km (<-3 km preferred) with respect to the MOLA geoid that can support the delivery of large payloads. They required that slopes be <5° over a 10 m length scale, and the chance of impacting a rock greater than 0.5 m high (1 m diameter) should be <5%. The landing site must be radar reflective to enable measurement of the distance to the surface [].

Apparently, the mindset of the Golombek team was influenced by SpaceX's ambitions to go well beyond making initial landings on Mars. They said: “Multiple separate landing locations spaced within a few km of each other, to support the multiple missions needed to grow an outpost…” The present manuscript focuses on an approach for a first landed human mission to Mars that appears to be more affordable and technically feasible. Preparing for outposts seems premature at this juncture, considering that each Starship departure from LEO requires a dozen heavy lift launches for refueling in orbit.

Golombek, et al. [] argued that “Latitude must be <40° for solar power and thermal management, and closer to the equator is desirable.” They also said the landing site: “… must be close to significant deposits of water/ice.” These two constraints are not necessarily consistent, pending ground truth for observations from orbit. The great majority of putative accessible water/ice lies at latitudes near 40°N or above []. Furthermore, “closer to the equator” is not merely “desirable” but might almost be mandatory. Rapp and Inglevakis [] pointed out that the virtue of an equatorial site is solar power availability, warmer temperatures, less variability of temperature, some benefits to EDL, and important beneficial psychological effects on crew (almost always neglected in studies).

Golombek, et al. [] went on to list several references related to ice on Mars, implying widespread availability of accessible ice: “Hundreds of meters thick local ice deposits”. Rapp and Inglevakis [] reviewed all the available data on water on Mars and arrived at a less affirmative conclusion that putative accessibility of ice remains unverified by ground truth, and in any event, much of it might be at a greater depth than is practical to utilize. The limitation to ~40°N latitude confines the range of sites to a narrow range where accessibility might possibly occur.

The SpaceX Starship (and probably the Blue Origin counterpart as well) will revolutionize opportunities for human exploration of Mars by greatly expanding assets, capabilities, and infrastructure that can be landed on Mars affordably.

Elon Musk, on behalf of SpaceX, published several postings on the Internet, making very bold claims, some of which appear beyond feasibility in the short-term to mid-term. These include landing humans on Mars by 2028, producing propellants on Mars for return while the crew is on Mars, and a first landing with a crew of twelve delivered by two Starships at a location with easily accessible water, followed by additional infrastructure to hold thousands of people in a “settlement”. Very little, if any, discussion has been given to the activities of the landed crew on Mars. Exploration of Mars seems not to have been discussed at all.

The Starship, for all its benefits, carries with it a major limitation. To depart LEO with 1,200 MT of CH4 + O2 propellants, plus 100 MT of payload, thirteen heavy-lift launches would be implemented to fuel and load each Starship into orbit in LEO, and if (as seems likely) five Starships might be required for the first SpaceX mission to Mars, that would entail 65 heavy-lift launches, which seems unlikely to be manageable. For “settlements,” the number of required launches would become so great as to be unimaginable. The nature of fueling the Starship seems to put a cap on how many Starships could be used for any mission.

The SpaceX mission design is quite innovative and fascinating, using a single space vehicle to depart LEO, land on Mars, depart Mars, and finally end up in LEO (or, who knows, possibly land on Earth?). This eliminates the need for two additional space vehicles and a rendezvous maneuver, but it requires the use of less efficient CH4 + O2 propellants for trans-Mars injection from LEO, and it requires dependence on accessible water on Mars. A smaller mission can be enabled by the Starship, but avoiding the need for Mars water. This writer suspects that avoiding the need for Mars water is most important, but lacking serious, detailed systems engineering analysis, the question remains: Which is more costly, challenging, and risky: exploiting water on Mars to produce hundreds of tons of propellants vs. developing a Mars Ascent Vehicle and a Mars Return Vehicle and executing a rendezvous and crew transfer maneuver? See Appendix 2 for further discussion.

Over the past ten years, several teams in the NASA community explored requirements for a landing site for a human mission on Mars. This culminated in a summary paper published in 2022 []. They clarified the requirements for a landing site in several aspects, such as elevation, winds, slope, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, and surface strength, and they searched for sites that might fit those requirements. Since they assumed the mission would require indigenous Mars water to produce propellants for the return trip from Mars, the need for large amounts of water on Mars became a commanding requirement, and they only searched for potential sites that might have Mars water, and looked within that range to find specific sites that appeared to fit requirements for aspects such as elevation, winds, slope, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, and surface strength. They searched the literature on observations and inferences of accessible water on Mars and chose regions at the lowest latitude, typically near 40°N. They would have preferred sites at lower latitudes, but the probability of finding accessible water ice would be much lower. The view in the NASA community seems to be that the probability of finding accessible ice near 40°N is high, but a recent review of accessible water on Mars is more uncertain []. Recently, an in-depth study was conducted of potential landing sites for a human mission to Mars that requires indigenous Mars water []. This study included consideration of terrain, temperature, radiation, dust, and potential water availability. They developed a multi-factor suitability index and estimated that index across the greater part of Mars. The suitability index was maximum across a wide swath of Mars between 30°N and 60°N, mainly influenced by the putative availability of water.

The discussion of landing sites for human missions to Mars depends critically on the vision one has for the extent and scope of how human missions to Mars will evolve in the mid-term. The vision expressed by Elon Musk on behalf of SpaceX involves colonization of Mars with thousands of people living in “outposts” or “settlements”. As a first step, they proposed landing a crew of twelve using two Starships, each holding six crewmembers. Not much else was described about the mission, other than that return from Mars would be enabled by utilizing indigenous Mars ice to produce propellants for ascent and return. In some postings, it seemed to imply that propellants would be produced while the crew is on Mars – seemingly a reckless, risky approach compared to producing propellants robotically before the crew arrives. In that same vein, Golombek, et al. [] indicated a requirement for “Multiple separate landing locations spaced within a few km of each other, to support the multiple missions needed to grow an outpost, are required …” It is not exactly clear how many Starship trips to Mars would be required for the SpaceX mission but it seems possible the number would be 5 at the start. Since each Starship in LEO must be refueled a dozen times and provided with payload in LEO, that would entail 65 heavy lift launches from Earth, which seems unlikely to be feasible. With the preliminary mission appearing beyond the scope of feasibility, the establishment of an outpost based on a great number of Starship launches appears to be fantastic.

The Starship is a major advance, but the requirement for multiple refueling in LEO appears to cap the number of Starships that could be launched in any time period. That would limit the scope of human missions to Mars based on the Starship. Nevertheless, constrained human missions to Mars in the mid-term could be enabled by the use of Starships. Such a feasible human mission to Mars would employ a crew of six and avoid the need for indigenous Mars H2O. It seems likely that two water systems would be used for life support, one potable, and the other used for showers and cleaning. The non-potable water, representing more than half the water requirement, could be recycled fairly easily. Potable water for life support could be brought from Earth as part of a Starship’s payload.

Studies over the past fifteen years on landing sites for human missions to Mars have focused on sites where indigenous H2O might be available, indicating sites near 40°N latitude. These studies seem to relate to the SpaceX vision of large-scale landings leading to an outpost or settlement where people would do what? We think that such missions are unlikely to be feasible in the mid-term, and are not headed toward a viable goal anyway. Instead, we should utilize the Starship to enable a limited human mission to Mars, where the crew’s role is to manage a global exploration program based on control of remote assets for exploration and sample acquisition. We think that current studies of landing sites, seemingly influenced by visions of grandeur from Elon Musk, are peering too far into the future, while overlooking what might be more feasible in the shorter term.

The requirements for a landing site for a human mission to Mars can be divided into two parts. One generic part concerns aspects such as elevation, winds, slope, rock abundance, radar reflectivity, and surface strength. These have been clarified by studies in the NASA community. The other part is the requirement for accessible near-surface ice in great quantity to supply several hundred tons of ice for the production of propellants for the return trip from Mars. Any large-scale Mars venture, such as a “settlement” or an “outpost,” would require such Mars ice. Even the first landing of humans on Mars envisaged by SpaceX requires several hundred tons of accessible ice.

Recent analysis and preliminary identification of landing sites for a human mission to Mars by NASA personnel and teams place great importance on the need for accessible ice, and this limits their region of choice to latitudes near 40°N. A recent review of water on Mars suggests that the existence of accessible ice at those latitudes is uncertain and cannot yet be counted on without in situ verification.

Another approach for the first human mission to Mars avoids the need for Mars ice but introduces two additional space vehicles: the small Mars Ascent Vehicle and Mars Return Vehicle. It can probably be implemented with just two Starship landings on Mars and is claimed to be “faster, cheaper, better” and might be more appropriate for a near-term first human landing on Mars. It can land at any equatorial location that satisfies the other criteria.

Until the architecture of the first human landing on Mars is further clarified, the search for potential landing sites ought to be extended to equatorial regions with no accessible water.

The appropriate crew size for a human mission to Mars depends upon the nature of the mission, and is not settled in any case. In the earlier (1997 to 2009) NASA system analyses of human missions to Mars [,], discussions of crew size suggested a crew of six, but left open the possibility of a larger crew. In an effort to reduce cost, NASA also imagined a short-stay mission with a crew of 4, with 2 landed and 2 remaining in orbit, although it was not clear whether the two crewmembers in orbit served any purpose. The short-stay approach does not appear to provide much return on investment. Zubrin suggested a crew of four to minimize cost []. Most recently, SpaceX indicated a crew of 12 for the first human landing on Mars [,].

Several studies of crew size for a human mission to Mars provided a variety of results. Dudley-Rowley, et al. [] based on functionality of a group in confined, dangerous spaces concluded: “Overall, larger crews were less dysfunctional than smaller ones. The crew that demonstrated the least deviance, conflict, and dysfunction of all numbered about nine persons”.

Chaikin [] provided a review of many studies of crew size for a human mission to Mars, starting as early as the 1960s. The predominant value was 6, with good arguments for 8, and lesser support for 4. His conclusion was:

“How many people should NASA send to Mars? Finding the sweet spot between “too many to be doable” and “too few to enable crew survival and mission success” will always be a judgment call based on rigorous, clear-eyed assessments. But if there is one lesson to be learned from the work of all the brilliant minds who have faced the ultimate systems challenge for almost eight decades, it is that the human exploration of Mars is an Everest for our species, and we must never let ourselves be lured into underestimating the extraordinary and unprecedented demands of reaching the summit.”

There is good support for a minimum crew size of six, and we adopted that for this early study.

Every 26 months (or so), the Earth and Mars are positioned for a minimum ∆v transfer from Earth to Mars. As the spacecraft travels to Mars, the Earth (moving angularly faster than Mars in its orbit) moves away from Mars, making a return trip difficult. Depending on the trip time to and from Mars, an appropriate window will open for a minimum ∆v transfer from Mars to Earth. Generally, this requires something like 500+ days of residence at Mars. That is why missions described in this paper, as well as almost all serious mission plans for Mars, involve the so-called “long stay” []. Alternatively, one can conceive of a short-stay mission of about 30 days or less at Mars (so-called “plant the flag and run”), but the return on investment is low, and the return trip requires high velocity coupled to a Venus flyby [].

The water demand for human life support was discussed by Jones [,] and Rapp [,,]. As Rapp pointed out, a detailed literature search yields a few historical statements of requirements lacking support showing detailed data or analysis. There does not seem to be serious, credible data-based requirements for water, and those estimates that do exist are typically contradictory. Water requirements for crew members are given as kg/CM/day. The estimates provided in this paper represent interpolations between existing estimates, combined with common sense. For a crew of six in a ~500-day stay on Mars, the total water consumption is huge. NASA needs to fill this vacuum of information.

To the extent that wastewater on Mars (as well as in transit) can be recycled, the water requirement can potentially be significantly reduced. The experience of cycling on the ISS provides some insight. However, the ISS cycling system required frequent “orbital replacement units” for subsystems that either fail or use up their resources, and would not be appropriate for Mars. It is widely thought that it should be possible to recycle wastewater, recovering at least 90% of pure water, but that has never been demonstrated with long life and high reliability. If one were to divide water between potable (for drinking and cooking) vs. water for washing and showering, it seems that the water used for washing and showering, lacking urine and feces and other wastes, would be easier to recycle. We have assumed that 90% recycling of shower/washing water should be possible. Jones [,] and Rapp [,,] provide additional information.

Propellant mass estimates are based on well-known values of ∆v for various transfers using the so-called “rocket equation”. For ascent in the DRA-6 mission concept, the masses and propellant requirements are given by Rapp [] based on a very detailed study by Polsgrove, et al. []. Polsgrove, et al. Used a crew of four, and Rapp scaled it to a crew of six.

Unlike delivery to Mars, return from Mars does not require a large mass of infrastructure and equipment. The payload is mainly crew plus some samples taken from Mars. The earlier system studies for a human mission to Mars typically utilized a system where the relatively massive Earth Return Vehicle (ERV) was never landed on Mars, and did not have to lift off from Mars. It was inserted into Mars orbit, and a relatively small capsule was used to deliver crew and Mars samples to rendezvous with the ERV and transfer crew and payload to the ERV []. This avoided the much greater propellant requirement that would have been needed had the ERV launched for the Mars surface. Accordingly, the mission concept DRA-6 adopted this approach.

Alternatively, one could consider direct return from the surface of Mars. Zubrin suggested this as an alternative []. In direct return, the ERV lands on the Mars surface and lifts off to go directly to LEO. The SpaceX version of this approach utilizes the same Starship that delivered crew to Mars as the return vehicle [,]. This has the advantage that no ascent capsule or distinct ERV need be designed, fabricated, and deployed. The downside is that a large mass of propellant is required for direct return of the massive Starship that must overcome the high ∆v for ascent from Mars. It is not feasible to deliver the propellant from Earth, so it would have to be produced from indigenous resources (CO2 and H2O) on Mars. While the CO2 is ubiquitous, the need for H2O would limit the choice of landing sites to around 40°N or higher. There are several disadvantages to higher latitudes, such as inadequate solar energy and the psychological impact of the weak sun in winter. The search for accessible water, followed by in situ validation, mining demonstration, processing demonstration, and propellant production, would require several sequential missions spaced by the 26-month spacing of launch opportunities. While SpaceX publications suggested that propellants for return would be produced while the crew is on Mars, that would be very risky, and the preliminary steps would still be needed.

Apparently, SpaceX believes that producing heavy masses of propellants on Mars is preferable to the DRA-6 approach, but no analysis has been published. This very important trade remains uncertain due to a lack of specific data on cost, complexity, and risk.

SpaceX posted several webpages describing aspects of their intended mission to Mars, but these roughly describe the Starship and transport to and from Mars. The context of all these postings is that the early landing is a prelude to much larger-scale missions leading to outposts, settlements, and colonies with large populations of up to thousands. The first landing is not necessarily aimed at exploration, but rather to inform on mission aspects relevant to large-scale future missions.

DRA-5 provided lists of science objectives, but this was mainly “what”, not “how”. While it was imagined that a long-distance, pressurized rover would allow exploration over a region of hundreds of km, the prospects for such a vehicle are uncertain. Nor is it clear how such a putative vehicle would be deployed and how crewmembers would utilize it for exploration.

Stoker, et al. [] developed a science strategy for human exploration of Mars, but it dealt with “what”, not “how”.

The report, A Science Strategy for the Human Exploration of Mars, identifies 11 top science objectives for human Mars missions and outlines four campaigns of missions to achieve them. NASA’s science and exploration directorates commissioned the study. These also deal with “what”, not “how” [].

The highest-priority objective was searching for evidence of past or present life on Mars. Other priorities vary from Martian climate and geology to characterizing resources for future missions and assessing the effects of the Martian environment on crew health, plants, and animals.

Stuster, et al. [] defined tasks the crew must do on Mars, but did not discuss exploration.

Based on an extensive literature search, there does not seem to be much information on how a human crew should best explore Mars.

Here, we propose that rover-based assets be distributed across Mars at attractive sites, and these assets be managed by the human crew at the main base using a pair of communications satellites in orbit around Mars. By reducing communication time between the rover and the human from~ 40 minutes to a few seconds, far more can be accomplished across a much wider swath of area. We also propose that samples be delivered periodically from remote sites to the main base for analysis. That requires a technology that does not yet exist, but it ought to be easier to develop than a pressurized long-distance rover for humans.

Zubrin R. The case for Mars. New York (NY): Simon and Schuster. 2011.

Platoff A. Eyes on the red planet: human Mars mission planning, 1952–1970. NASA Contractor Report NASA/CR-2001-208928. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2001.

Portree DSF. Humans to Mars: fifty years of mission planning, 1950–2000. Monographs in Aerospace History, no. 21. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Policy and Plans, NASA Headquarters; 2001.

Rapp D. Human missions to Mars. 3rd ed. Heidelberg (Germany): Springer-Praxis Books; 2023.

Drake BG. Human exploration of Mars: design reference architecture 5.0 (DRA 5.0). NASA Special Publication SP-2009-566. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2009.

Jones HW. The recent large reduction in space launch costs. In: Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2018 Jul 8–12; Albuquerque, NM. Paper ICES-2018-81.

Jones HW. Take material to space or make it there? In: Proceedings of the ASCEND Conference; 2023; Las Vegas, NV.

Making humanity interplanetary [Internet]. Hawthorne (CA): SpaceX; 2024 [cited 2026 Feb 7].

com. SpaceX's Mars colony plan: how Elon Musk plans to build a million-person Martian city [Internet]. New York (NY): Space.com; [cited 2026 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.space.com/37200-read-elon-musk-spacex-mars-colony-plan.html

Rapp D. Will SpaceX send humans to Mars in 2028? IgMin Res. 2024 Dec 13;2(12):969–983. doi:10.61927/igmin274.Rapp D. Preparing for SpaceX mission to Mars. IgMin Res. 2025 Mar 4;3(3):123–132. doi:10.61927/igmin292.

Maiwald V, Bauerfeind M, Fälker S, Westphal B, Bach C. About the feasibility of SpaceX's human exploration of Mars mission scenario with Starship. Sci Rep. 2024 May 23;14(1):11804. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54012-0. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 5;14(1):20718. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-71955-6. PMID: 38782962; PMCID: PMC11116405.

Rapp D, Inglezakis V. Accessible H2O on Mars: a critical review of current knowledge. IgMin Res. 2025 Nov 25;3(11):407–439. doi:10.61927/igmin322.

Rapp D. Human missions to Mars using the Starship. IgMin Res. 2025 Aug 6;3(8):268–277. doi:10.61927/igmin308.

Bussey B, Hoffman SJ. Human Mars landing site and impacts on Mars surface operations. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Aerospace Conference; 2016; Big Sky, MT. doi:10.1109/AERO.2016.7500775.

Golombek M, Williams N, Wooster P, et al. SpaceX Starship landing sites on Mars. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference; 2021; Virtual. LPI Contribution No. 2548.

Rapp D. Mars ascent propellants and life support resources: take it or make it? IgMin Res. 2024 Jul 29;2(7):673–682. doi:10.61927/igmin232.

Golombek MP, Grant JA, Parker TJ, et al. Selection of the Mars Exploration Rover landing sites. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(E12):8072. doi:10.1029/2003JE002074.

Golombek M, Rapp D. Size-frequency distributions of rocks on Mars and Earth analog sites: implications for future landed missions. J Geophys Res. 1997;102(E2):4117–4129. doi:10.1029/96JE03319.

Golombek MA, Huertas D, Kipp D, Calef F. Detection and characterization of rocks and rock size-frequency distributions at the final four Mars Science Laboratory landing sites. Mars J. 2012;7:1–22. doi:10.1555/mars.2012.0001.

Zhu S, Zhao B, Yu Y, Shi X. Habitat site selection on Mars: suitability analysis and mapping. Acta Astronaut. 2025;226:1–22. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2024.11.019.

Hoffman SJ, Kaplan DI. Human exploration of Mars: the reference mission of NASA Mars exploration (DRM-3). NASA Special Publication SP-6107. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1997.

Rucker M. NASA’s Strategic Analysis Cycle 2021 (SAC21) human Mars architecture. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference; 2022 Mar 7; Big Sky, MT.

Rucker M, Craig DA, Burke LM, Chai PR, Chappell MB, et al. NASA’s Strategic Analysis Cycle 2021 (SAC21) human Mars architecture. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2022. NASA Report.

Dudley-Rowley M, Whitney S, Bishop A. Crew size, composition, and time: implications for exploration design. In: Proceedings of the AIAA SPACE 2002 Conference & Exposition; 2002. AIAA-2002-6111.

Chaikin A. Humans to Mars, but how many? A historical review of crew size determinations for Mars missions. NASA Contractor Report NASA/CR-20240015749. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2024.

Polsgrove T, Thomas D, Sutherlin S, et al. Mars ascent vehicle design for human exploration. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2019. NASA Report.

Stoker CR, McKay CP, Haberle RM, Andersen DT. Science strategy for human exploration of Mars. Adv Space Res. 1992;12:79–90.

Cowing K. A science strategy for the human exploration of Mars [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2025 [cited 2026 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.nationalacademies.org/publications/28594

Stuster J, Adolf J, Byrne V, Greene M. Human exploration of Mars: preliminary lists of crew tasks. NASA Contractor Report NASA/CR-2018-220043. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2018.

Rapp D. Landing Site Selection for the First Human Mission to Mars. IgMin Res. February 09, 2026; 4(2): 06-075. IgMin ID: igmin333; DOI:10.61927/igmin333; Available at: igmin.link/p333

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

Independent Researcher, South Pasadena, California, USA

Address Correspondence:

Donald Rapp, Independent Researcher, South Pasadena, California, USA, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Rapp D. Landing Site Selection for the First Human Mission to Mars. IgMin Res. February 09, 2026; 4(2): 06-075. IgMin ID: igmin333; DOI:10.61927/igmin333; Available at: igmin.link/p333

Copyright: This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Plan for return from Mars using a capsule to deliv...

Figure 1: Plan for return from Mars using a capsule to deliv...

Figure 2: Three steps in direct return from Mars....

Figure 2: Three steps in direct return from Mars....

Zubrin R. The case for Mars. New York (NY): Simon and Schuster. 2011.

Platoff A. Eyes on the red planet: human Mars mission planning, 1952–1970. NASA Contractor Report NASA/CR-2001-208928. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2001.

Portree DSF. Humans to Mars: fifty years of mission planning, 1950–2000. Monographs in Aerospace History, no. 21. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Policy and Plans, NASA Headquarters; 2001.

Rapp D. Human missions to Mars. 3rd ed. Heidelberg (Germany): Springer-Praxis Books; 2023.

Drake BG. Human exploration of Mars: design reference architecture 5.0 (DRA 5.0). NASA Special Publication SP-2009-566. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2009.

Jones HW. The recent large reduction in space launch costs. In: Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems; 2018 Jul 8–12; Albuquerque, NM. Paper ICES-2018-81.

Jones HW. Take material to space or make it there? In: Proceedings of the ASCEND Conference; 2023; Las Vegas, NV.

Making humanity interplanetary [Internet]. Hawthorne (CA): SpaceX; 2024 [cited 2026 Feb 7].

com. SpaceX's Mars colony plan: how Elon Musk plans to build a million-person Martian city [Internet]. New York (NY): Space.com; [cited 2026 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.space.com/37200-read-elon-musk-spacex-mars-colony-plan.html

Rapp D. Will SpaceX send humans to Mars in 2028? IgMin Res. 2024 Dec 13;2(12):969–983. doi:10.61927/igmin274.Rapp D. Preparing for SpaceX mission to Mars. IgMin Res. 2025 Mar 4;3(3):123–132. doi:10.61927/igmin292.

Maiwald V, Bauerfeind M, Fälker S, Westphal B, Bach C. About the feasibility of SpaceX's human exploration of Mars mission scenario with Starship. Sci Rep. 2024 May 23;14(1):11804. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-54012-0. Erratum in: Sci Rep. 2024 Sep 5;14(1):20718. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-71955-6. PMID: 38782962; PMCID: PMC11116405.

Rapp D, Inglezakis V. Accessible H2O on Mars: a critical review of current knowledge. IgMin Res. 2025 Nov 25;3(11):407–439. doi:10.61927/igmin322.

Rapp D. Human missions to Mars using the Starship. IgMin Res. 2025 Aug 6;3(8):268–277. doi:10.61927/igmin308.

Bussey B, Hoffman SJ. Human Mars landing site and impacts on Mars surface operations. In: Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Aerospace Conference; 2016; Big Sky, MT. doi:10.1109/AERO.2016.7500775.

Golombek M, Williams N, Wooster P, et al. SpaceX Starship landing sites on Mars. In: Proceedings of the 52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference; 2021; Virtual. LPI Contribution No. 2548.

Rapp D. Mars ascent propellants and life support resources: take it or make it? IgMin Res. 2024 Jul 29;2(7):673–682. doi:10.61927/igmin232.

Golombek MP, Grant JA, Parker TJ, et al. Selection of the Mars Exploration Rover landing sites. J Geophys Res. 2003;108(E12):8072. doi:10.1029/2003JE002074.

Golombek M, Rapp D. Size-frequency distributions of rocks on Mars and Earth analog sites: implications for future landed missions. J Geophys Res. 1997;102(E2):4117–4129. doi:10.1029/96JE03319.

Golombek MA, Huertas D, Kipp D, Calef F. Detection and characterization of rocks and rock size-frequency distributions at the final four Mars Science Laboratory landing sites. Mars J. 2012;7:1–22. doi:10.1555/mars.2012.0001.

Zhu S, Zhao B, Yu Y, Shi X. Habitat site selection on Mars: suitability analysis and mapping. Acta Astronaut. 2025;226:1–22. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2024.11.019.

Hoffman SJ, Kaplan DI. Human exploration of Mars: the reference mission of NASA Mars exploration (DRM-3). NASA Special Publication SP-6107. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 1997.

Rucker M. NASA’s Strategic Analysis Cycle 2021 (SAC21) human Mars architecture. In: Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Aerospace Conference; 2022 Mar 7; Big Sky, MT.

Rucker M, Craig DA, Burke LM, Chai PR, Chappell MB, et al. NASA’s Strategic Analysis Cycle 2021 (SAC21) human Mars architecture. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2022. NASA Report.

Dudley-Rowley M, Whitney S, Bishop A. Crew size, composition, and time: implications for exploration design. In: Proceedings of the AIAA SPACE 2002 Conference & Exposition; 2002. AIAA-2002-6111.

Chaikin A. Humans to Mars, but how many? A historical review of crew size determinations for Mars missions. NASA Contractor Report NASA/CR-20240015749. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2024.

Polsgrove T, Thomas D, Sutherlin S, et al. Mars ascent vehicle design for human exploration. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2019. NASA Report.

Stoker CR, McKay CP, Haberle RM, Andersen DT. Science strategy for human exploration of Mars. Adv Space Res. 1992;12:79–90.

Cowing K. A science strategy for the human exploration of Mars [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2025 [cited 2026 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.nationalacademies.org/publications/28594

Stuster J, Adolf J, Byrne V, Greene M. Human exploration of Mars: preliminary lists of crew tasks. NASA Contractor Report NASA/CR-2018-220043. Washington (DC): National Aeronautics and Space Administration; 2018.